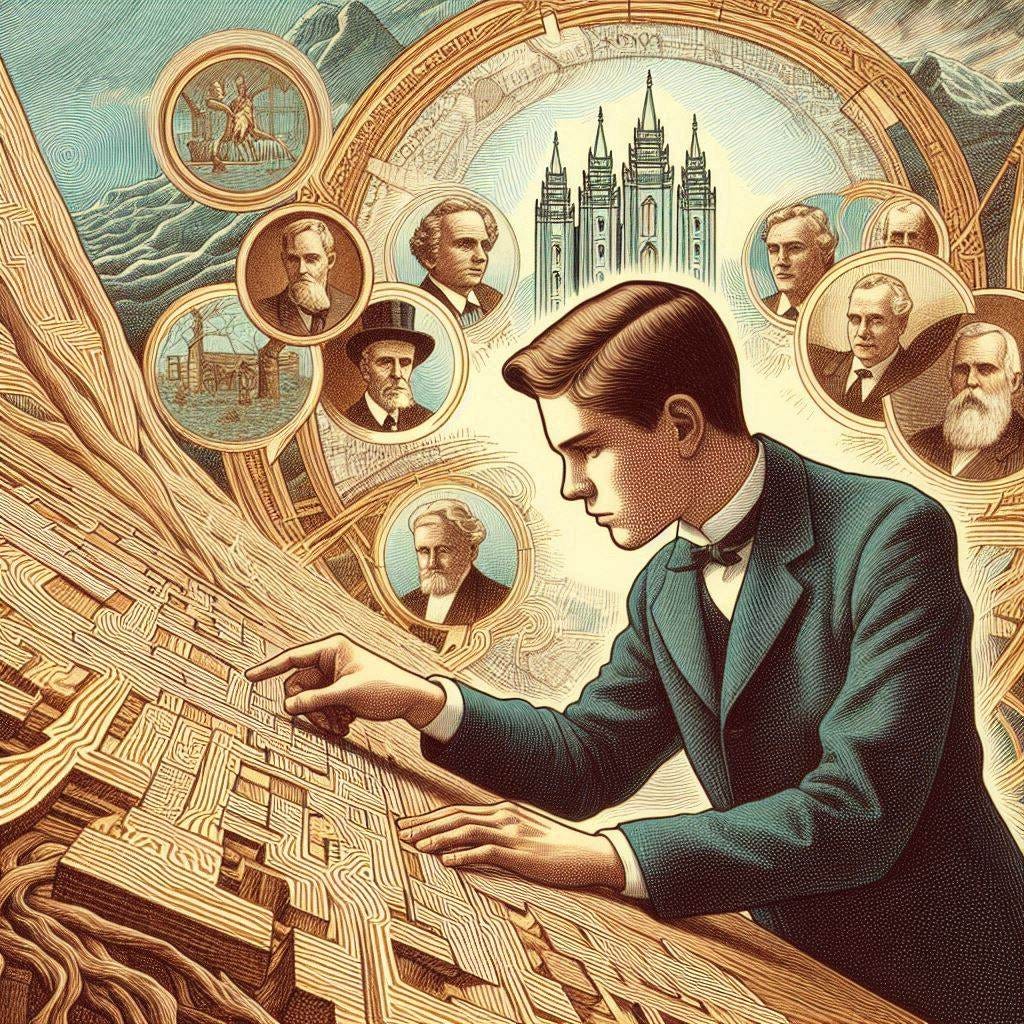

What Convinced Me: Stories from my path out of Mormonism

My first essays tracing the woodgrains

Content note: As the title implies, this post contains a frank and thorough account of my decision to leave the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. While I aim to approach the topic respectfully, it’s impossible to write without touching on a lot of areas that are sensitive for church members. If you are among my LDS friends, family, or other readers, please use your discretion as to whether to read or skip this particular post.

Note as well that this is an essay series written over a span of several months and as a result is much longer than my typical posts. I elected to centralize them on a single page to avoid drowning out other posts, but each essay is mostly self-contained and the series was not written with an eye towards being read in a single sitting.

Seven and a half years ago, I made the most consequential decision of my life: to step away from the religion that had defined my family and my culture for seven generations, the religion to which I had devoted tens of thousands of hours of my life. It was not something I did casually or carelessly, nor was it a sudden flip from belief to non-belief. Rather, it was the culmination of a long-standing, serious effort to decide where I stood, one that started when I dove into all the apologetic and counter-apologetic arguments as a teen, continued throughout an exhaustive effort to consider my faith on its own terms during my LDS mission, and ended in two years of spiritual paralysis1 before I could admit to myself that I only had one real option.

I created this username the day I decided to seriously consider leaving the church, and it’s not a coincidence either that I kept it or that I began to write in much greater depth about cultural and political topics after doing so. While I remained committed to Mormonism, I felt strongly that if my thoughts were out of line with it, I was the one who was wrong. As I came more and more into my own views and realized their divergence from LDS orthodoxy, I felt less and less sure about speaking up. In addition to this, while I was LDS I experienced the internet as fundamentally hostile territory and anticipated facing vitriol and exclusion if I presented my faith-influenced frame frankly (aided by a few harsh experiences as a young teenager). These compounded to leave me paralyzed, at once worried that I could not adequately align with my faith and that people would reject me if I did.

All of that fell away the day I stepped out on my own. I spent a couple of months writing obsessively about my path away from the faith, telling the stories—particularly mission stories—that lingered in my mind as I was trying to decide. And then, abruptly, I stopped and moved onto other topics, satisfied that I had said enough. Even now, I’m not terribly fond of the place I wrote them—Reddit’s /r/exmormon served as a useful transition spot for me, but as with any place centered around opposing something, it creates an incentive to center the most vitriolic and hostile people and boost the worst experiences with what it opposes, creating an atmosphere that was wholly intolerable for me as a believing Mormon and that remains barely tolerable for me even now. But it served its role.

The essays that follow are those stories, the first things I ever wrote under the name Tracing Woodgrains. They’re written for a Mormon-familiar audience, so I’ll lightly annotate them for others. I hope you enjoy.

As a side note, these come much closer to the form of a personal biography than a detached analysis of the faith on its merits. When it comes to the latter, I endorse the work of John T. Prince without reservation. Prince is a former BYU chemistry professor and by far the best post-Mormon at speaking respectfully and directly to Mormons about the faith, and I owe him a debt of gratitude both for how he responded to me personally and for providing perhaps the only analysis of LDS truth claims I really feel confident endorsing.

Convince Me

This post will be almost illegible to people unfamiliar with Mormonism; I’ve included it for its significance to my story and added links to context as relevant. It was the first post I wrote under this name.

This2 isn't a place I expected to post, really ever. I'm an active member. It's my two-year anniversary since my mission. I left and came back the same doubting, uncertain but striving individual. I read all about church history questions long ago and wasn't too worried, and always told myself that as long as I got a confirmation that I recognized as from God, I would be content in faith. Well, I saw a lot of spiritually building, strengthening things, and a good number of apparently unanswerable questions and unresolvable situations to balance it out, and none of that confirmation that I was seeking. I've spent the past two years trying to figure out where to go next, and right now am willing to test the idea that it's false.

I've read a lot of what you all have to say, and a lot of responses to it. The CES letter3 and a couple of common rebuttals and your responses to the rebuttals, alongside a lot of /u/curious_mormon's work, have been the most recent ones for me. There are several compelling "smoking guns," many situations that I don't have a good answer to and have known that I'm unsure about for a while. But I wouldn't be posting here if I was fully convinced.

Here's the thing: in all the conversations, all the rebuttals, every post and analysis and mocking joke, I have not seen a compelling enough explanation for the Book of Mormon. You're all familiar with Elder Holland's talk. I remain more convinced by the things he talks about and others' points of the difficulty of constructing a work of the length, detail, and theological insight of the book within the constraints provided.

There are three legitimate points raised that have opened me to the possibility of something more. I'll name them so you don't need to repeat them:

The Isaiah chapters—errors and historic evidence of multiple authors of Isaiah

Textual similarities in The Late War

Potential anachronisms and lack of historical evidence

The translation method is a non-issue for me. Similarities with View of the Hebrews seem a stretch. The Book of Abraham and the Kinderhook plates are their own issues and I am satisfied with the information I have on them. Despite raised concerns, the witnesses remain as strong positive evidence, but they are not my concern here.

In short, I want to see how the Book of Mormon could have been produced by man, especially with intent to deceive. Despite all I've read and heard and my lack of personally satisfying spiritual experiences, Church doctrine has been a rich source of inspiration and ideas for me, many passages in the Book of Mormon are powerful and thought-provoking on each read-through (Alma 32, the story of Moroni, Mosiah 2-5, 2 Nephi 2, 4, and the last few chapters, and Alma 40-42 are some of the best examples)4. I've always had questions, and they've always stopped short at my confidence that there is no good explanation for the Book of Mormon other than it being from God.

Specific questions to resolve:

How was it produced in the timeframe required?

Who had the skill and background knowledge to write it? If not Joseph, what would keep them from speaking up?

Where could the doctrinal ideas have come from, and what am I to make of the beauty and power of some of them?

I'm sure you all know the weight of even considering something like this from my position. I'm here, I'm listening, and I am as genuine in my search for truth as I have ever been. So go ahead. Convince me.

I will be available to respond once more in a few hours.

This led to a wide-ranging discussion. The obviously and overwhelmingly best response came from John T. Prince and can be seen in full here. As an active member, my impression of exmormons was that they were almost uniformly rude, unreasonable, and superficial or heavily motivated in their criticism. Prince’s response to me made it impossible for me to maintain that picture and left me with nowhere to hide.

Before I continue with other posts covering subsequent events, I should get to the stories leading up to that moment.

Doubt in the Missionary Training Center

Note: Provo’s Missionary Training Center (MTC) is the primary location prospective missionaries go to learn the basics of being a missionary and, if studying a language, the basics of the foreign language. I spent less than two weeks there.

Well, I'm back again with my fourth post in about as many days. I guess that's what having your worldview shattered will do to you. […]5

Before I left, I stood up in front of my entire home congregation and told them I didn't know the Church was true, but I wanted it to be true and was willing to commit two years of my life to find out. With that as not just the primary but the only thing on my mind, I walked into the MTC with two goals:

Be exactly, unflinchingly obedient and fully committed every step of the way as a missionary

Be exactly, unflinchingly honest in what I did and did not know.

You can imagine the sort of chaos that would cause for a young, doubting missionary.

Here are some samples of my journal from the MTC: "Everyone is so upbeat here. That's not a compliment. ... Day in, day out, I'm told to learn by the Spirit, feel the Spirit, pay attention to the Spirit, and so forth. It's be nice if I could, but as of now it's just frustrating. It's funny to think that the missionary lessons probably wouldn't work to bring me to the Gospel. We're asked to commit people to baptism during the first lesson. That's crazy. No way I could make a life change that quickly. I guess it works for some, though. Trust in the Lord for direction."

"I know, I need to stay positive and eager, but [my teacher] is just so... perky. I hate perkiness. His lessons are unhelpful, his answers to questions unsatisfying. I wrote a lovely little rant about the instruction to always invite investigators to be baptized during the first lesson. The gist is that I hate the idea and have a hard time believing it came from God. ... I love individual study. I've been reading through the Book of Mormon, and it's satisfying and enriching. I wish I had a stronger testimony6 of it, though. The words are beautiful, but part of me constantly analyzes the truth claims."

"Everyone here is much more spiritual than I am. It's a bit discouraging. I have a lot of work to do. I'm trying, but I just don't understand. ... It's frustrating, because I'm so much more knowledgeable, so I have to keep myself from thinking, 'Oh, they don't deserve it.' They do, of course, but... well, I wish I did."

That instruction to invite to baptism on the first lesson was my first point of major disagreement in my mission, and I asked my teachers quite a bit about it. The instructor referenced above told me to pray so I could understand that policy came from God. I prayed. I still hated the policy. I told him that, and it turns out he didn't have a plan B. Meanwhile, another teacher decided that the best solution to me not having a spiritual witness of the Book of Mormon was to have me kneel down and pray with him about it, just in case the dozen times I prayed on my own about it in the MTC were insufficient. That went just as well as the other prayer. I stood up, asked what to do if I still didn't have an answer, and was told, "uh, keep trying. You're on the right path."

I still can't stand that policy on baptism. The investigation of truth is so personal and so vital and so time-consuming, and we as missionaries were to insist that any earnest seeker would be able to commit to a transformation of faith after a 30-minute presentation and one prayer. It stood contrary to everything I felt about how the process of gaining faith should work and would work for me. Bonus points for the wonderful lesson from my teacher that if I had questions, the solution was to pray until I realized why I was wrong. That time in the MTC started (continued, really, but everything before hardly seems to matter now) a trend of constantly wondering how I could purify myself more, how I could ask more sincerely or with more faith, what wording I could change or lever I could pull or button I could press to switch prayer from a process of crying into the void to the legitimate means of gaining truth that I was about to try to teach everybody for two years it was.

You might be wondering, after reading this, how I possibly stayed in the mission field for two years. I really did like studying the scriptures, except for the parts I didn't, and I was in the MTC during the General Conference where President Uchtdorf said "We respect all who earnestly search for truth" and Elder Holland talked about struggles of mental illness. As skeptical as I was about the truth of a lot of it, I was confident in the good of most of it, realized how much good two years of trying to help people could do for an introverted and self-centered kid who talked to almost nobody but close friends, and felt like I needed to do everything in my power to receive an answer from God before falling away.

So I stayed—leaving was honestly never an option, just like serving was never an option, not because I felt forced or pressured but because a mission had always seemed like as natural and inevitable a step in life as attending high school. And in staying, I created an ever-growing stack of questions that I was ever more desperate for answers for while simultaneously building the ideas and inspiration that I expect to use as foundation for almost everything I do through my life, met some of the best people I have ever been around, and had at once the most worthwhile and most damaging experience of my life.

If you're wondering how it ended, it involved me staring and almost screaming down my last mission president7 in an interview until he told me that my last companionship8 was not inspired, it was not "exactly where God had wanted me to be," that it was a choice he had made and a risk he had taken that didn't pan out. But that's a story for another time.

When an “Investigator” Ruined Moroni’s Promise for Me

Note: “Investigator” is the LDS missionary term for people considering whether to join the faith. Moroni’s promise is the claim central to Mormonism that people can pray to learn the truth of Mormonism.

Well, I'm back once more. One reason I'm sharing these stories is that my journey to the point I'm at now seems in a sense unique: historical evidence had very little to do with it. Church culture was a minor factor at best. I was determined to allow the church to stand or fall for me on spiritual grounds, and always, always it came back to Moroni's promise. Pray, let God answer, and know in your heart that the Book of Mormon is true. Good enough for me, until the promise fell flat on its face.

One memory that stands out is when a companion of mine asked if when I prayed asking about the Book of Mormon, I was doing so with complete faith. I told him that it was guarded, but present, since my actions had failed to produce a recognizable answer so often, but I was trying. In response, he asked what it would take for me to let that guard down and really, completely trust in God. My answer, more or less, was this: “Then what would I do if nothing happened?”

You all already know: when you’re looking to God and he doesn’t answer you, there are any number of answers people will give. The most common instinct is to say that perhaps you didn’t pray with enough faith. Well, I wanted to know that God was there more than I’ve wanted anything else. From that conversation, I started looking for opportunities to express more and more faith, trusting that God would fulfill his promises. One of the biggest ones I was seeking was the chance to independently test Moroni’s promise: to find someone not connected to the church, someone who didn’t have all the baggage I had built up around it, who would read the Book of Mormon and pray about it so I could learn from watching if and how Moroni’s promise worked.

It took a while, surprisingly, to find someone willing to actually read more than a page or two of the Book of Mormon. Funny thing, that. But finally, we ran into someone who I let myself be certain was “one of the people God had sent me there to find:” a Christian guy I’ll call Max at the university I was studying, a psych student who was fascinated by religion of all sorts and extremely open to conversation. He agreed to read the Book of Mormon without hesitation. Over only a couple of weeks, he read the whole book, then the Pearl of Great Price9, Our Search for Happiness10, and several sections we recommended from the Doctrine & Covenants11. He took an intellectual, analytical approach to it all, rather than, ah, the spiritual sort that missionaries prefer to have people take, but there he was: someone finally investigating the church’s claims as honestly and completely as I could ask, using the sources that we provided and willing to take the test that we as missionaries proposed. When we asked him if he would be baptized if he felt it was true, he said that of course he would.

And then he prayed about it and said that he honestly felt like it wasn’t true.

Well, that’s not how it works. And I wasn’t ready to let it end that way. He was a friend of mine at this point and the most thorough investigator I’d been able to talk with, and that was not the way things were supposed to go. So I prayed, and fasted, and talked with my companion, and that’s when I broke one of my personal mission rules: I said something that wasn’t strictly honest.

I already mentioned I really wanted to have faith. I tore voraciously through every story I could find of conversion “miracles”, of missionaries doing something extraordinary and people responding in extraordinary ways, and that was Going To Happen and I wasn’t just going to let it go. So we met with Max again, and asked him to pray about the Book of Mormon again—verbally, sincerely, with us—and promised him that God would respond if he did so.

That’s the part I regret. I knew already why my faith was guarded. I knew perfectly well what would happen if someone made that promise to me. But I fought to convince myself that for someone who was just learning, someone who didn’t have all the background I had, it would be different.

Well, the story ended the only way it could end: Max, ever straightforward, agreed to our terms. We sat together, talked a bit, read a couple of verses, and had him pray. It was a thoughtful prayer, an honest one. We all paused for a few seconds afterwards. Then Max looked up and said, “I’m really sorry, guys. I just don’t think it’s true.”

And that’s it. He wasn’t baptized. He didn’t “see the error of his ways.” And we, as missionaries, were left speechless, because there was nothing more we could say or do. God had remained silent. Our promise, and Moroni’s promise, had fallen flat.

My mission president told us when I called him, distraught and worried, that Max must not have had honest intent, that perhaps he was looking for the wrong things as he read, that sometimes people just aren’t prepared. I just stared off into space and thought again about the conversation where my companion asked why I couldn’t express a moment of unguarded faith.

That was why.

Board Shorts and a Plaid Shirt

This one still haunts me.12

Okay, a lot of my stories still haunt me. This is all raw for me. None of it has really healed over, nothing has really been figured out. This, time, though, I was the vehicle for delivering a message I did not believe at the time, do not believe now, and felt uneasy and embarrassed as I delivered it. But I delivered it, because that was my job.

It's time for the story of Eric, who I never knew very well and who certainly doesn't remember my name, but who I still every once in a while think about and want to go apologize to.

See, Eric did not fit the comfortable baseline mold of a church member. He was converted some two years before I arrived in his area, a long-haired, eccentric guy who wore board shorts and plaid shirts every time we saw him. He was introverted and didn't trust or care to meet too many new people. He was also smart, spiritually thirsty and searching for peace.

And he stopped coming to church because the stake13 wanted more Melchizedek Priesthood14 holders so the ward15 wanted him to pass the sacrament so the bishop16 strongly encouraged him to wear a white shirt and tie to church.

Remember what I said about board shorts and plaid shirts? Those weren't an accident. Eric told us how he felt like too often people used clothes to create artificial distinctions, how he didn't want to create a false front for people. He quoted the scriptures talking about costly apparel and looking on outward appearance. A bit defensive, a bit angry, he spoke frankly about how these clothes were the best he owned, because they were the only ones he owned, that they were clean and well maintained and that this was a matter of principle for him.

I can say at least I pleaded his case. I checked for wiggle room, explained his situation, asked for an exception. But my mission president, normally a deeply caring man and someone who I will always look up to as an example in all regards of life, insisted. It was such a small thing, he said. You can pick up a clean white shirt and tie from the thrift store for a few dollars, he said. A ward member could lend one. But it was needed.

It was never about the cost, though. It was the message. It was what wearing those clothes represented to Eric that was the problem. So I went back to him and did my duty, and gave him the official church answer and told him the suggestions proposed and just sort of looked at him and shrugged. He argued the point for a bit and then never picked up the phone for us again.

I'm not going to run into Eric again, so in lieu of apologizing in person, let me do so here: you were right. I couldn't say it at the time. I was an Official Messenger, and I had an unambiguous message to deliver. But it was the wrong message and it chased you away when you were looking for peace and acceptance. We should have been able to provide it. We shouldn't have been restricted by our own cultural expectations in telling you what you needed to wear, but we were and are and I was and it was the wrong answer and I knew it but I gave it anyway, and who could blame you for going away? You saw clearly.

It was such a small thing, a blip of a story in a much larger context. Sometimes, though, the small things stick.

There is such a helplessness in giving an answer you know is wrong to someone you know is right.

“I had to see a counselor after I lost my faith”

Hey, how about that time I went through the Old Testament to write down every time God killed someone?

An investigator and close friend of mine had found the story of Nephi killing Laban, and was deeply, personally angry with it. Perhaps his story will come later. He was a fascinating guy, a modern-day Greek philosopher attending the college we worked around. I was determined to answer his question thoroughly, honestly, and effectively.

...and, quite frankly, it was a chance to try to resolve and/or express my own frustration with the Old Testament. Really, if there's been any less spiritual work written than the historical portions of the Old Testament, I haven't heard of it. It was quite a list, and I hated it. It lingered on my desk for a few days, staring grimly back at me. Anyway, things went on, I answered his question but not my own, I asked around and the general consensus was, "That's an excellent question. Toss it on the shelf17" and several months passed.

Then I met Mat. He was smoking a hookah on the porch when we walked by, and was startlingly happy to engage in conversation. Turns out he grew up a deeply religious Coptic Orthodox member, but after a struggle that you're all familiar with, lost his faith several years back. When we met him, he was a Bible Studies student at the local university. We snapped into teaching mode, and when we described the Book of Mormon, he—before we could even ask him—interrupted and said, "Where can I find a copy of this 'Book of the Mormon'?"

There's no more exciting question for missionaries, and—in a recurring theme for my mission and these stories—I felt certain that, if God sent us certain places to find certain people, he had sent me there to find Mat. I was going to do everything to teach him and encourage him to test the Book of Mormon.

I had gotten in way over my head.

See, when we sat down with Mat and started talking in earnest, he shared with us one of the core reasons he had stopped believing in his own faith: The Old Testament, and how God acts in it.

How on Earth are you supposed to answer someone's deeply felt, soul-wounding question when you have the same unresolved question kicking around your head? How do you respond? How do you respond when he goes on to tell you that he doesn't mention it much but he had to go through counselling for a while when he stopped believing in his religion, how he still pauses at various churches and prays asking for any indication that God wants him on a different path?

Oh, we still tried. We talked him through it, pointed out that perhaps our talking to him was that indication he was looking for, read through some of the Book of Mormon with him...

but he had already seen too much. We all, on some level, knew it. I remember reflecting at the time how impossible it seemed for someone who had traveled the path he traveled—without ever encountering the church—to ever be converted. I heard the pain in his story, the sorrow in his voice as he discussed his journey, his earnest continued study and precise questions, and it was clear to me that if anybody was an "earnest seeker of truth," he was. I could find no fault in his path. And I couldn't help him.

That's the problem with tossing things up on the shelf as a missionary. Every once in a while, you encounter someone whose shelf broke in the same location and pattern as yours is fracturing. All we could do, then, was talk, and learn, and listen, and go away mumbling something about planting a seed.

Wherever Mat is, I hope he is finding peace on his spiritual journey.

“If I wasn’t gay, I would join your church.”

Sexuality is one of those issues I never really learned how to handle. Since I personally consider myself asexual, that sort of topic has always been a process of observing from a distance more than one of personal passion. It is one of the defining issues of our time, though, and inevitably I found myself needing to answer questions about it on my mission, especially as the church related to gay marriage. Some of the abstractness I felt faded as I became personal friends with several gay people on my mission. The most memorable of those was Asher.

This is a happy story, by the way. It's one of the few I'll share with you all that was a genuinely good experience for all concerned. I share it because it was eye-opening, left a lasting impression, and stands to me as a thought-provoking experience from the perspective of Mormons and ex-mormons alike.

As fits such an unusual situation, we met Asher by showing up late to an appointment. It was with Max, actually, at the local university. While waiting for us, he struck up a conversation with the student at the next table over. We arrived, introduced ourselves, and found ourselves launched alongside Max into team-teaching someone who identified himself as a stateless, agnostic, gay gender studies student about our differing perspectives on Christianity.

It was absurd, and we all recognized it. Asher was openly and firmly wary of our beliefs, Max and us had different goals and perspectives as we were sharing about the same thing, and we were facing down possibly the single least likely demographic combination to have any interest in the church. Despite that, we kept at it, and we had a genuine, good conversation, and against our own and his initial expectations, all found ourselves wanting to meet again.

Running through the standard missionary lessons with him was unquestionably impossible, and we weren't going to try. Instead, he treated it as a sociology experiment of sorts. He asked us all sorts of questions—not all of them about faith. I remember one moment where he asked if it was okay to ask me something personal, I said sure, and he asked something like, "How often do you masturbate?" Was that the exact question? Not sure, but I kind of coughed and changed the subject quickly. It was not the sort of topic I knew how to address. At times we would turn it back to spiritual topics and found someone who was idealistic, hopeful towards some sort of spiritual truth, and genuine, but he was not keen to dwell in those areas.

He enjoyed the conversations as much as we did, though, and—again with the idea of a sociology-based perspective—even decided to attend church with us a couple of times. We sang "We are all enlisted" at the first church meeting he came to and—as he was, shockingly, something of a pacifist—he was outright angry with the overt war imagery in it. It was all a great intersection of people with completely different backgrounds, though, and I was a little disappointed to be transferred away and no longer be able to teach him, even though I didn't see anywhere teaching him could lead.

Luckily, though, I found out the rest of his story from the later missionaries there. Of all the people we talked to and were working with, he was—against all my expectations—one of the only people who kept meeting with missionaries for a while after we left. They tell me he kept coming to church almost every week for a while and had several powerful spiritual experiences, culminating in the title statement: "If I wasn't gay, I would join your church."

What a bittersweet thing to hear—from any perspective. It was inarguable. Oh, missionaries could try to press it because that's a missionary's job, but... well, this group knows better than any the conflict between the church and gay people. And neither I nor the other missionaries that met with him were going to force the issue. I took it then the same way I take it now: an open-minded student who is spiritually hungry finds a genuinely good community of people (which this ward was: it remains to this day my single favorite collection of people within the church) and some satisfying spiritual answers...

...that just happens to be wholly, irreconcilably incompatible with everything else in his life.

If he hadn't been gay, or the church hadn't made its stand so firmly, this would fit perfectly within the block of "faith-promoting, miraculous conversion stories" that returned missionaries love to share. As it was, it provided a few young people from wildly different backgrounds a chance for increased mutual understanding and friendship and stood as my first first-hand experience with the struggle between gay people and the church. It made me reflect fairly regularly on my own position and helped personalize an issue that this Utah kid who had never even really bothered to date (much less anything else) had previously only thought about in an abstract, detached sense. I still consider Asher a good friend.

The Leper, Cast Out

Members of the church are told constantly that their callings18 are from God. In General Conference and in lessons, in talks and in trainings, again and again the counsel is repeated that God puts people where he needs them, that he qualifies them for their positions, and that they will be blessed for obeying the leaders of the church even if they turn out to be wrong.

That teaching was the cause of the single greatest pain on my mission and my time in the church. It is a painful, dangerous teaching. Sometime, I'll tell my own story. This time, though, I want to tell worse, sadder, and more deeply cutting than my own: the story of Brother McDaniels from one of my wards. It was my first exposure to how damaging a determined obedience to church teachings could be.

The first time I met him, without knowing anything about him and only knowing our job as missionaries was to inspire members into missionary work and give us referrals, I assumed from the thoughts he shared and how quickly he welcomed us that he was a fully active member. I taught a stirring, brief lesson and invited him Boldly to invite a friend to be taught by us. Yeah right, he said curtly and coldly escorted us from his house a few minutes later.

See, Brother McDaniels wasn't coming to church, even though he was as converted as a member comes. He was an intellectual, witty former Bishopric member, married in the temple, returned missionary, thoroughly convinced of the church's truthfulness...

...and, oh yeah, did I mention he contracted leprosy on his mission that manifested some twenty years later? Now he was basically homebound, and the idea of referring someone to the missionaries was laughable because he never met anyone.

The church wasn't the strongest where I was, and as a result tended to overuse its most faithful members. Saying yes to one calling and fulfilling it well usually meant another, and another. The perception that someone was a strong member meant that would not rest again.

So what happens when one of those members has a rare disease rendering his continued movement increasingly painful, forcing him to step back hours and eventually quit his job, and taking him further and further from a normal life?

The bishop drags his feet on allowing Brother McDaniels' family access to church aid, feels inspired to assign him another calling as a family history coordinator on top of the role in the bishopric he is currently serving, later feels inspired to unceremoniously drag him into his office and lecture him on duty before abruptly releasing him from the bishopric, and then the ward continues asking for more—Sunday school lessons and so forth. The whole time, in his telling, Brother McDaniels did his best to follow what was asked of him and to serve and take on the responsibilities he was asked to take on. He was a converted member, after all. That was his job, even if his life was literally falling apart around him.

And still he believed. He spoke with regret about how he used to know the scriptures like the back of his hand and study them every day, and now was reading the Epic of Gilgamesh instead and feeling torn. He talked about how he knew he needed to return to church, and he wanted to return to church, but there was such a tangle of issues in the way. Throughout, one thing was cuttingly clear: a man who had a good life and dedicated his life to the church found only continued demands, not support, when everything crashed down around him. Perfect obedience, in his case, would have meant subjecting himself to a torturous situation.

When you believe, though, when you're really committed to the gospel, willing disobedience is a torture in itself. Consciously choosing to not attend church (and he made it clear he could still attend, but chose not to) meant breaking the Sabbath. Turning down the Bishop's requests would have been a lack of faith in his heaven-appointed leaders. Even listening to missionaries ask for a stupid referral and having no way to give it to them is a reminder that you are not helping to grow the kingdom of God. Guilt and sorrow were written into his face and into every part of his story. Even as he told us how various nerves were irreparably damaged, how his days were pained and his nights were sleepless, he was expressing his hope to have the courage to return to church.

"Is there no balm in Gilead; is there no physician there?" For Brother McDaniels, there wasn't, and any answers or support we could provide as missionaries seemed woefully inadequate. What do you do when what is supposed to be an anchor keeping someone stable is instead the anchor dragging them down? How can a missionary help a wounded soul injured explicitly because of the member's devotion to God? How do you promise blessings for obedience when the blessings expressly and loudly failed to come when he obeyed?

That was a big weight on my mind in my mission. I saw the church work well in many people's lives, but when it stopped working, there was nobody there to say "It's okay to take a break. It's fine to step away. You won't be working against God. You won't be failing your faith." There's just a horde of friendly arms reaching out, a hundred cheerful, loving mouths saying "Any time you feel ready to come back to church, you'll be welcome!" and a double helping of guilt and sorrow. The only answer we could give was come to church, just come along and things will work out somehow.

Let me say again: The leprosy was from his mission.

The Ex-Mormon’s Return

"Everything I was doing, as far as my lifestyle diverged from the church, I always felt like the Mormon kid doing those things."

You know, all this recent talk about the story about an ex-Mormon attorney who returned to the church reminded me of another story.

This one's one of my favorites. It was one of my favorite faith-building moments when it happened, one of the brightest spots looking back on my mission immediately, and one of the most thought-provoking as I consider things again from a new perspective.

Yes, it's time for the story of Alexander, the ex-Mormon who called us up and told us he wanted to return to church. Yeah, he was a true convert to anti-mormonism. Yep, he genuinely wanted to go back to church. And his return, in the end, went much better than many here might expect, if not quite as well as active members would have hoped to build a perfect faith-promoting story(tm).

Let's dive in.

You're never quite sure what to expect as a missionary when a member calls you up and tells you they have someone who wants to return to church. Half the time, the "person who wants to return" looks at you like you're crazy when you mention it; another good chunk, nobody even picks up the phone.

Have I ever mentioned how rarely people pick up the phone when you're calling them as a missionary? Story for another time.

This time, though, a sweet and sincere older lady asked us to get in contact with her son. She said he'd fallen away from the church at fourteen and had shown no interest in returning for the past sixteen years, but had a spiritual awakening recently and wanted to explore the possibility of coming back. And so we called the number provided, and a perfectly sane and reasonable guy answered confirming the story and agreeing to meet up with us.

So we talked to him. Cool, cool guy. He'd fit right into [r/exmormon], and in fact said he participated in several groups like [it]. He'd never been particularly inclined towards church things, and at the age of fourteen dove into all the information available online and came away perfectly confident and content that the church was not true, that his family was wrong, and that it was time to step away and not look back. He knew all the history, read all the evidence, was passionate about LGBT causes... all of it. So he moved on with his life, got a job catching people cheating in online poker, and was perfectly content without any spiritual element in his life.

A couple years back, his sister died, and a couple of things shifted in his life that made him start looking around for that spiritual element again. He looked towards Buddhism and searched around some other faiths for a while, but as he put it, he kept comparing everything he went to back to what he grew up with, and eventually he decided to give it another try. He identified strongly with ideas of a gospel of personal progression, a church that expected action and improvement, and related concepts.

He also gave the quote above about how he never stopped "feeling Mormon," in a sense, and talked about how there are some things it's really hard to internally let go of—things like the idea of a pre-existence that keep kicking around. The talk "Come, Join With Us" opened the doors for him and made him feel like perhaps there was a place in the church for him. He expressed a hope that things would or could shift to be a bit more open and liberal on some issues important to him.

I suppose it was a bad sign for my own activity in the church that I was more comfortable talking to him and understood his perspective more easily than that of many active members. It was strange and kind of cool for both sides, I think—on the one, an ex-Mormon who is considering returning to a faith he left behind long ago, on another, a missionary companionship facing down and thinking about all the same issues that drew Alexander away and willing to talk about them openly and frankly. At last, I thought, someone who understands the issues, who wrestles with the questions I wrestle with, and at the same time feels the same draw to the church I do.

We all agreed: the church didn't have all the answers, we personally didn't really know them, but where he was it made sense to go back and try awhile longer, to see if he got again the spiritual nourishment he was hungry for and to consider again the aspects of the doctrine he appreciated. We read to him from D&C 121:34-46—verses that to this day I love and appreciate as a guide for how to act in any leadership position—when he talked about wanting to prepare for the Melchizedek Priesthood. He mentioned candidly how a 10% paycut would bite, but that he bought plenty that he didn't need and wasn't suffering for cash. It was a frank and fascinating conversation with someone who was genuinely interested in returning to church.

Unfortunately for my direct involvement in the story, he ended up going to a different ward than the one I was in, but he sent us a text from his first time back at church. I'll paraphrase it: "I went to church in the city ward today and it was AWESOME! I felt the Spirit really strongly and everyone was so welcoming and good. Thanks for talking with me."

Talk about a faith-building, pat-yourselves-on-the-back moment for missionaries. Wrap it up, write home, tell the story of a lost sheep finding his way back, call it a day.

We all know the world isn't that simple. I had a chance to catch up with Alexander later in my mission, and he talked about how excommunications of a couple of prominent Mormon activists (looking back, I believe he was talking about Kate Kelly and/or John Dehlin) took a lot of the wind out of his sails and how difficult it was to find a spot in the church, especially outside of Utah, as a single 31-year-old. He had a good experience on his return and a lot of what he remembered and appreciated, he still appreciated when he came back. Ultimately, though, it became clear to him once again: the church is not an easy place to be for one in his position, and makes a lot of moves that push against his sensibilities. The message of welcoming he heard in "Come, Join With Us" and the various doctrines he appreciated and still identified with in the church was counterbalanced by every push back from all the issues faced today by an intellectual, liberal Mormon.

That's it, as far as I know. That's the story of the 16-year departure, return, and redeparture of Alexander from the church, the miracle-story-turned-sad-reminder for a young, searching missionary.

So, in answer to the question posed by some here: Yes, sometimes ex-Mormons do want to return to church. In fact, there are even times when it seems they can find a comfortable place within the faith and apply some doctrine they still hold close.

And then the church doubles down.

The “Golden Investigator”

A “golden investigator” is someone who, in the eyes of missionaries, is a perfect potential convert to Mormonism.

Look, my last story19 was pretty bleak. It was asking to be told, but it was not the happiest of moments for anyone involved. It is possible, in pausing for recollections like that, to fall back into grim patterns of thought. Partly to guard against that, partly because his story deserves to be told, I'd like to share the story of Ambrose, one of the best men I know.

The image of him I will always hold is the time we were walking back from a discussion in a park. We were in a rougher part of town, streets littered with broken bottles, beer cans, and other debris. As he walked, he would pause frequently and bend to pick up the bottles littering the ground, mumbling that he didn't want cats to step on them and be hurt.

The man was like a monk. His story came out in bits and pieces during our conversations in the park, how he lived with his elderly mother and ran a shelter for stray animals at his home with her. How he had started out studying a harder science, but had changed his course of study to psychology and social work because he wanted to make a genuine difference for people. His introversion and withdrawal from most social situations. Most intriguingly for missionaries, his reasoned and careful faith.

See, we met him in a missionary's dream scenario. We were in our car headed to a visit, saw him nearby, and my companion felt like we should talk to him. During the conversation, he described himself as a Christian, but one who didn't attend any specific church: not out of apathy, since he was highly religious in word and action. Rather, he said he read the Bible on his own and disagreed with some of their teachings... the trinity, for example.

Words like that are absolute music to missionaries. As we met, though, I grew more and more quietly frustrated—not with him, but with the lessons and way we were supposed to teach him. Here was a man who was thoughtful and good, who asked sincere questions and meant every word he said, who agreed with our beliefs in key areas. We were going through a simplistic, set pattern of lessons and commitments and expecting him to change everything in a month or two. It was not really meeting his needs, but the church doesn't have a mechanism for slow and thoughtful investigation. It demands commitments and baptisms now.

We had incredible conversations, though. He thought, asked questions, and listened. We shared our stories and he shared his, talking once about how he spent a lot of time on various discussion forums working towards and presenting views of a reasoned faith. During one of our meetings, he shared an observation and question that he considered among the most troubling for a faithful person. That question has since become a core one of my own, and so I'll share it.

He pointed out that he'd spent a lot of time reading, discussing, and thinking about faith. He talked about how some people were content to just accept wherever they were, how they simply weren't intellectually open or curious. Those he understood for the question he was to ask. But what about the rest? There were people he had met online, in person, through stories, that were clearly earnest seekers of truth.

Why did they believe so many different things if there is one true path? How can earnest, seeking, thoughtful people be so wildly divergent in their beliefs after examining the same data? Because these people exist, how can you be truly confident in your own belief?

I'm not here to pretend it's a unique observation or question. What I will say is that it is a critical one. Glib, simple answers do not do it justice. I shared some thoughts at that time, but I thought a whole lot more about it, because one of the church's fundamental claims is that God will lead earnest searchers to the church if they just give it a chance. And here was a gentle reminder, from the among the most earnest searchers and practitioners of faith, that things were simply not that simple. Unfortunately, this point does not fit in the standard narrative and so is rarely given more than brief or glib treatment.

That question is where the story ends. I was transferred from the area, and he met with the missionaries one more time afterwards—for my sake, I think, since I'd asked him to keep meeting with them—but the missionary-prescribed path of discussion was simply not particularly meaningful for one in his position. With luck, I will find his email at some point and get in contact, but our meeting served its purpose:

Here was a remarkable, sincere, religious man who was willing to do what we asked and test our faith, one who was a "golden" investigator by missionary standards, who agreed with some of the church's fundamental principles

and he saw what we had and thought about it and talked over it and then walked away, continuing on his hopeful path.

The next sequential story is that of my chosen title, previously reproduced on my Substack.

The Bitter End

If there is any defining story in my journey out of the church, this is it. This was the moment that tore my soul apart, that made me lose all sense of peace within the church, that left me spiritually paralyzed for the next two years.

It is not a happy story. It does not have a bright lining. It was a horrible, senseless experience that I have spent a great deal of time since trying to categorize, trying to explain, trying to overcome. If it is long, it is because this is the first time I have told it in full, and I desperately want to convey some of the feeling of a moment that requires context.

This is the story of the time I put every ounce of faith I had left into God, then was left reeling in the aftermath. And it starts with a conversation on transfer day20:

"Are you certain? Are you absolutely certain this is inspired?"

I feel bad for the poor APs21. I felt bad for them then. But I was a tired kid at the end of a long mission and on my last shreds of sanity. I started with absolute commitment to being an extraordinary missionary, to doing all in my power and putting my heart in the hands of a God I was trying to learn to trust. Things had started badly and corrected with a couple of high points in the first year that made me feel like things could be getting somewhere. After the start, though? Not a lot. The past year had been a slow decline as I realized that I did not have the testimony to lead a companionship to success, would not allow myself any degree of disobedience, and could not resolve attendant tensions within my companionships.

From the start, one of my biggest goals was learn to be close with those working alongside me, something that did not come naturally to me. For a host of reasons, that entire year had followed a cycle of having a tricky companionship, trying and failing to resolve tensions, and running away to a new area. Any hint of investigators progressing towards baptism had faded. We had some meaningful experiences with less active members22, but in the past few months, those were gone as well. I had gone from being a zone leader at nine months to begging for a release23 and transfer, to having weekly phone calls with the area mental health specialist. When I say I was at the end of my rope, believe me, I mean it.

There was one idea, one single point, that kept me clinging on to hope: God was in charge. He put missionaries exactly where they needed to be, with exactly who they needed to be with, in order to find exactly the people they needed to talk to. All that was impossible to understand would be resolved in time. Even as I struggled to know whether to believe in God, I told myself that if I just mustered what faith I had and went forward, he would guide me, and things would work out. It was my lifeline. But time was running out. I was down to my last transfer, and I'd spent the previous two with a missionary who I'll call Elder Ma (names have been changed for the privacy of individuals concerned). He first idolized me as an ideal companion and former leader of his, then grew to hate me as he realized how human I was. Three days of venomous silence towards me followed by blowing up in my face and screaming louder than I'd known people could scream marked the end of a desperate transfer. I was genuinely afraid of being around him.

And then we got transfer news. Two missionaries, coming into our area. Our companionship would be split up—one new missionary with me, one with the companion I'd had such troubles with. One of the incoming missionaries, Elder Kim, was a close friend of mine, one who I got along near-perfectly with and loved working alongside. The other, Elder Cao, had been transferred out of the area alongside his companion just two transfers prior, leaving me and Elder Ma to clean up the mess. Reports were that he was depressed, frustrated with trying to learn English, unsure of his own testimony, and had significant psychological problems attached specifically to certain aspects of that area.

No prizes for guessing which one was assigned to Elder Ma and which to me.

A new mission president had just arrived in the mission, and hey, why not try new things, right?

So there I was, staring down the APs, daring them to tell me that this was from God. They told me that our new president was an inspired man. I called him personally and expressed my concern. He said he thought it would work.

What else was there to do? I prayed for humility, patience, and faith. I told myself I would repent of my doubts and simply work to be the best companion I could. I donned my smiling mask, welcomed Elder Cao to the area, and got busy with the work. I was even cooking meals for him, because apparently that's a way for friends to support each other? I never cook. And for about a week and a half, things were bright! They were happy. The work was moving forward a bit. It looked like we might actually be successful.

Two weeks from that, I was staring at my phone, willing myself to call the mission president, admit failure, and beg for an emergency transfer24. Elder Cao had gone non-communicative and wouldn't participate in study or work. My own depression had clawed its way back in. Nothing was working, everything had gone to pieces, and all I had left to hope for was a few weeks of peaceful work to end my mission and nurse my wounds. I had failed. My hope for my mission was extinguished.

Now, how do you think a mission president would respond to a desperate, sobbing missionary explaining that he just couldn't make things work with his companion, he tried, everything fell apart, please just get him out of there? If you answered "Move both of them to an apartment right next to the mission home, tell them not to leave their apartment except for a few specific tasks and to just study all day," congratulations, you get a gold star, because that is exactly what that inspired servant of God did.

Thought experiment: what happens when you put two depressed, stressed people with a language and communication barrier in the same room with nothing to do all day after one of them has begged to be moved and while he just wants to finish by doing some semblance of important work?

Apparently in our mission president's inspired mind, the answer was "experience a therapeutic, healing, and restful time where everything will get better." Let's check in with reality: my companion still wouldn't talk to me, started going places without caring whether I was following, and reached a point where I told him I was hungry and needed to grab some food from a nearby store and he just said "No" and walked in the opposite direction. Finally, after two days of this, I told him I appreciated him, I wanted to talk with him, wanted to work through things with him, would do anything I could. He ignored me. I asked him to say something, anything. He ignored me and walked away. I knew you can't force conversations, but knew at the same time that we needed to work together and the status quo was unmaintainable, so I pushed the issue again. He grabbed the phone, called the APs, and said, "My companion is trying to talk to me, but I don't want to talk." That's all he would say. No explanation. No context. Nothing. He just said he didn't want to talk, he didn't want to say why, he would not talk, again and again for some half an hour.

I mean, on the bright side, that was enough to get the emergency transfer I had asked for a week before.

That was two weeks before the end of my mission.

I called my mission president. I asked for a meeting. And I sat down, and asked him to be perfectly honest with me, and tell me, please, please, if that was inspired.

I give him credit for his answer, at least. He sensed my desperation, I think, and was open. He told me no, it was not inspired. He said he had been working from incomplete information and made a mistake. He said he put that elder with me because, as he said, "I knew you had been struggling with depression so I thought you might be able to work with him." He said he was inspired in maybe half his calls, but the others were just basically filling in the gaps. We said a little bit more, and then he went away, and I sat in the shattered remnants of my mission.

Here, in my own words, is my reaction to the news—that of a missionary trying to think positively, trying to do things the way God tells him to, having just been told by the person he had trusted to administer God's will that there was nothing there at the single most critical point:

Now, all of [the things he said about inspiration] are clear to anyone who's really looking, and they weren't news to me, but it was such a relief to hear it said! But with that relief comes a lurking feeling of adriftness. In a way, the simple church answers are nice. It's nice to feel that every calling is from God, that the Church is a purely uplifting force, and so on. But it's not Truth, and must be discarded at some point in the approach. For most of us most of the time, it's just people doing their thing the best they can, with a nudge here and a poke there if it's really crucial. It means that not every Church story will have a happy ending in the moment we see it. Not every investigator who reads the Book of Mormon will feel a magical wave of power. Not every testimony or talk is specifically inspired to touch some audience members. Ward councils are usually dysfunctional through no spiritual fault of participants.

These are the ways things work, in everything, really. I had hoped the Church was somehow different, against evidences received. And, well, there are some differences and the spirit's whisper is real, and promptings do happen and are beautiful. But there is more.

That was my brighter moment. My darker one went more like this:

"Oh, you say you're trapped within your own mind and watching your last hopes for your mission crumble around you? Well yeah, okay, that assignment was probably not inspired. You still want to finish strong, you say? Cool. We'll stick you right... here, and just have you study all day while we kick ideas around. Yep, you're still with your silent friend, so there's no way to get out of your own head now! See you in two weeks!"

Is it really that hard to say, "Well, what do you think would work?" after all else has failed?

It's easy to say God will make more of your life than you will, but what do you do when you've put your heart into letting Him take control and the car wrecks itself?

And that's how it ended. I put my trust in God, bet on what I'd been taught of him against all my intuition and reason, and came away feeling utterly broken and empty.

My last two weeks were spent drifting aimlessly through my area, getting up on time and studying and walking around city streets until I had fulfilled the bare minimum of my duty. My dreams of being a remarkable missionary or even a very good one had been torn to pieces, tossed to the ground, and stomped on. My hope of gaining a witness of the church was shattered. There was nothing left to do but go home and try to move beyond whatever was left. I drifted through final words of wisdom and preparation, mustered up one last testimony for my fellow missionaries, answered the temple recommend25 questions in as skeptical a way as I could manage while my mission president listened without caring, sat through a few empty parting thoughts from him, and stepped forward into two years of trying to come to terms with all that had happened.

Now, I guess I'm finally coming to terms with it. The light is dawning. It's just not the light I asked for or ever wanted to see.

Adrift A Year Post-Mission

Note: This is the earliest writing in the bunch, and it was written while I was a believer to an audience of believing Mormons. Presented here as the most natural place sequentially.

I can’t stand writing about this, because I have so very much to say but no idea how to properly convey any of it. I’m simply tired of being so very spiritually adrift and alone.

I returned from my mission a year ago. I left for it unrefined, full of questions and doubt, only sure that I knew the Church was good and hoping to figure out the rest along the way. Two years later, I walked away deeply appreciative of several spiritual high points, but bruised by the lows and somehow more conflicted about it all than when I started. Since then, I have simply been drifting, confused and clueless about my next step.

It might be best to start with what I believe and know: No explanation for the Book of Mormon holds up to examination except that it was from God. Joseph Smith and the early Saints were flawed but deeply earnest and devoted in their cause. Many verses of scripture in all the Standard Works contain powerful and remarkable truths that consistently move me as I read them and talk about them. Our current prophet and apostles are good men of remarkable integrity and faith who see and speak clearly. And we, as individuals and a collective Church, are generally good people who are trying to do right. These are the anchors, the foundations of my faith.

But then I hear quotes like the following from Mother Teresa (as referenced in this recent Conference talk), and I identify so firmly with them that I practically collapse in tears: “Please pray specially for me that I may not spoil His work and that Our Lord may show Himself—for there is such terrible darkness within me, as if everything was dead. It has been like this more or less from the time I started ‘the work.’ Ask Our Lord to give me courage.”

I have read the Book of Mormon in as much an attitude of faith as I can muster. I have prayed, earnestly and repeatedly, asking for further light from God. Each time I pray it is as if I am crying into a void, hoping vainly for an answer. There is no comfort or strength there. On my mission, I was determined to be exact, to be faithful, to Do Things Right and let God guide. A few amazing moments occurred—things that still give me strength—but more and more towards the end, things began to descend into a struggle that was at times emotionally devastating and nightmarish. My initial hope that I would find evidence that God was guiding me and those around me in His church was met by a confounding sequence of events that seemed to confirm the opposite. Even though the vast majority of “problems” ex-members or people of other faiths raise do not worry me at all, I continue to find no answers to my own most pressing questions of faith, and have reluctantly concluded that for many of them, there are no answers yet. Meanwhile, the week-to-week reality of being a member and attending church has become frustrating and dull in a way I never really anticipated.

As of now, I find myself in an impossible position. On the one hand, there are truths I cannot avoid even if I wanted to. On the other, there are pressing questions that I cannot explain away or pretend have been answered. I find myself going through the motions of everything related to the Gospel despite yearning to be a spiritual and a good person, in large part because every time I do even a bit more than going through the emotions, it hurts. A lot. Writing this hurts, and it’s the most meaningful spiritual thing I’ve done in months. It drains me.

I talked to my mission presidents while I was serving. I’ve talked with my bishops since. We’ve had good conversations, but both they and I knew each time that we’d had to leave most problems unresolved. I’ve talked with my family members and closest friends, only to realize that the people closest to me are wrestling with similar situations. Each conversation brings the assurance that at least I am sane, but pushes spiritual peace yet further away.

Of course I don’t expect to magically get all the answers from an online forum. But where I am is unsustainable, and if there is one thing forums are good for, it is the chance to draw from a wealth of different people’s life experiences. All of what I’ve written serves, in a way, as the question I would pose to all of you, but to summarize:

What does one do when Peter’s famous words to Christ in the aftermath of disciples turning away become not an affirmation of faith, but an expression of helplessness: “Lord, to whom shall we go? thou hast the words of eternal life.” Or, in other words, what do you do when your place in the Church is uncomfortable and unstable, but you recognize that there is no other place to turn?

EDIT: It's pretty interesting for me to see how many people who have left the Church have independently messaged me about what I've said here. It's up to five now, so I'll say here a bit of what I've told them: I really am not who you're looking for. Whatever concerns I have, I love the Gospel and have found little of value in the materials you always recommend to your potential investigators. It is possible to question some things without believing that it all must be wrong and I ought to walk away from it. There's a reason I posted this in /r/latterdaysaints and not elsewhere.

And with that, we’re back to the creation of the name Tracing Woodgrains and the request to “Convince Me.” All subsequent posts are from the early days of my path out of Mormonism.

You Convinced Me

Hey, everyone. A few of you probably read my post from a few days ago, found here. I laid out my thoughts, you all responded, and I thought a lot about my position and what I really believe.

And I was wrong. That's where I'll start. I've had a lot of questions, worries, and doubts about church doctrine for years, but I was scared of losing something so core to me and always optimistic that somehow, some way, they'd get resolved. I dove into apologetic arguments 5 years ago and read the essays26 the day they came out. I was being sincere when I mentioned that the Book of Mormon was my core sticking point. It always got skimmed over in the analyses I read, and in truth I didn't feel like seeking out a lot of them. But it weighed as the main counterbalance for a flood of other concerns. It's funny, because not a lot of them are cultural or historical. In compiling what bothered me, I had only mission materials to work from (since, well, I was a missionary at the time), and they were all I really cared to consider there. There were enough sticking points for me that I didn't have time to worry about the rest of it. I clung fast to all evidences of faith I found, though, and let them anchor me for a long time. I passively ignored things and shut things out, and I was wrong, and I was careless.

But, well, you all convinced me. There were a lot of good points raised. Reading about Mormon quoting directly from verses added by scribes after the fact to Mark and the Deutero-Isaiah chapters being included in Second Nephi was the point at which I had no more, really, to say. It's a hard point to argue, it was new information to me... you can consider it the straw that broke the camel's back. Vogel and statistical analyses of the Book of Mormon text were also extremely informative.

I still don't know where exactly I go from here. I'm not angry with the church, just tired and wanting to figure out what is really true. It's been such a core part of my life that I hardly know who to be out of its context—as immersed in church culture as I've been my whole life, every perspective, every belief, virtually every idea that I have is connected to the church in one way or another. I'll probably even keep attending for a while—my ward doesn't have a backup organist. But my mind is out, and all the little hints, all the cascading clues and nagging irregularities that piled up are sitting ready to be resolved.

I have a lot to write here—stories that pulled me towards this path, worries that kept building up, the path of adjusting my life and sense of self. I want to get my mind straightened out. I've been so tired of desperately trying to align my beliefs to the church's. It was a struggle my entire mission, it's been a struggle since, but I never wanted to do anything halfway and I was going to be the best church member I could if it killed me. My first post here was after my main decision point, honestly: when I was being a good member, I couldn't ever bring myself to come here or read anything you all said without revulsion. But I sat down a few times last week trying to write a mission retrospective and broke down crying each time as I remembered how hard it had been, how mentally torn I had felt. I realized then that the longer I spent trying to resolve things through a lens of faith, the longer that feeling of being confused and torn would persist.

I'm one of the lucky ones. I went away from church schools a while back, so I don't have that hanging over my head. My family knows the struggle I've gone through spiritually and they're supportive of me even though they're active members. I already told them, in fact. My mom's first reaction was "Yeah, that doesn't really surprise me" and they told me they love me and want to see me find spiritual peace and be happy. My closest friends in church have plenty of their own doubts and are okay with me doing what I see as best. I'm sure some people will freak out, but I've never hidden my beliefs or perspectives.

Anyway, thanks, guys. Several of you provided really valuable perspectives and did a lot to help me even begin to imagine the possibility of leaving the church (special thanks to /u/bwv549 and /u/I_am_a_real_hooman for really taking me seriously and taking the time to share in-depth and thorough perspectives that helped me reframe things). Others of you still make me recoil by instinct with some of what you say and how you approach things, frankly, but I'm growing to understand your perspectives.

It's going to be an interesting ride. It's not what I had planned, but I'm slowly starting to think it might be for the best. It will be a while before I know what any of my perspectives are and what life will look like moving forward, but that's okay, I guess.

Of Moving On: Experiences with Unitarian Universalists

As I mentioned in my initial post about being convinced, despite my current position of uncertainty, engaging with spiritual things remains important for me. So, in between sessions of General Conference (which I still listened to, since I want to be certain and to make it absolutely clear that I am not running away from opportunities to let God speak to me), I went and visited a local Unitarian Universalist church. It was my first time at one of their services, my first time even thinking about attending.

Okay, you know all those stories about missionaries meeting someone, dragging them to church, and them talking about how it feels like coming home, like filling in something that was missing in their lives, and so on?

Yeah, it was like that.

I don't know whether I'll keep attending there and know hardly anything about them, but my experience there was the first really spiritual time I've had at a church service since my mission. They had beautiful classical music mixing with beautiful hymns in every break and throughout the worship service. Kids got to gather around for a story up front, then dismiss to classes instead of sitting through a service designed for adults. An SPCA representative stood up at the beginning and talked for a bit, and half their donation plate went to the SPCA that week. In all of the conversation and talks at the meeting, an overriding theme was the pursuit of goodness and truth. After the main meeting, various groups broke off to talk about helping social causes in the local area, answering questions about their practices, and so forth. Everywhere I looked was transparency—how much money they were looking to raise, where it was going and why, why they ran their meetings the way they did, and so on, was apparent not just through asking but openly displayed around their building.

And underlying all of it was the core message that I did not have to come to the same conclusions as anybody else in the building, an emphasis on asking the right questions rather than finding all the answers, the idea that intellectual curiosity and careful examination of everything were vital in an individual's spiritual quest. In short: every frustration that I had with three hours of repetitive, soporific meetings in which too often the sensation of doing real good seemed lost, with a culture of suffocating questions and encouraging conformity, and other disconnects attached to church faded away, while everything I loved about the idea of serving others, pursuing truth and right and benefiting from shared experience was preserved. The best part is that I can continue attending or leave with no attendant sense of compulsion or guilt.

One reason I have clung to the church for so long is the good I saw and see in it. I like the pursuit of spiritual truth. I am drawn to the idea of a community working together to do good. I love playing and hearing religious music. Things might change, but at least right now, I feel like quoting the unicorn from C.S. Lewis's The Last Battle when he goes to Aslan's country:

"I have come home at last! This is my real country! I belong here. This is the land I have been looking for all my life, though I never knew it till now. The reason why we loved the old Narnia is that it sometimes looked a little like this."

The reason I loved church at times is that it sometimes looked a little like what I saw today. I still don't know exactly where I'm headed, but every day things seem to get a bit brighter and paths for life in the wake of the church seem a little clearer and a little happier.

Here's hoping it continues. This is all still so new.

Note: It didn’t continue. I enjoyed my experience with the UUs, but ultimately concluded that groups would inevitably build a local consensus, that they’d snuck a specific dogma in through the back door while feeling like they were open, and that I didn’t particularly fit in with their implicit frame.

Church as a Non-Believer

I don't know why I'm so determined to make things this hard for myself, but, well, here I am. It was my first time to church since my recent change of perspective. I went there today to play the organ for them, stayed to tell my bishop my stance on things and see how he would respond to my questions, and stayed a whole lot longer as he tried to figure out what was wrong with me. I was and am torn about telling him, but my inclination is to be as open and honest about things as possible in hopes of achieving some sort of mutual understanding.

Oh, and I accidentally got in an argument about prophets in Sunday School, which I was attending while waiting for the bishop. I'm still not used to the new boundaries of what to say and what not to, and one of my comments touched an "apostasy warning" vein with a well-meaning senior missionary and, well, yeah. It was a bit discouraging to realize at every turn how much I disagree with on any given Sunday and how quickly I became "the guy in spiritual peril." I'm not so good at keeping my head down.

It might have been a mistake to meet with my bishop. I'm torn. On the one hand I want to make it absolutely clear that the standard reasons the church gives for people leaving do not apply. On the other, it makes a good, busy man take a lot of time and energy having no real idea what to say to me. Interesting conversation, though. I presented my story and core concerns. He realized pretty quickly that "read and pray" weren't going to cut it and had a really hard time figuring out how I could have prayed, gone to the temple, read the scriptures, and come away not believing. He tried to create an atmosphere to let the spirit testify to me by sharing various personal experiences and scriptures. I told him my questions remained. After a while he told me (very kindly) that the spirit prompted him to tell me I may be possessed by an evil spirit that is blocking me from receiving truth and that a priesthood blessing27 might help.

Eventually, though, he finally realized that an otherwise worthy, fully active member just did not believe any more. He asked me how he could help. I told him he could help by either providing likely impossible answers to my concerns and questions, telling me that the church didn't have answers to them, or by telling me it was okay not to believe and to leave. He took door number one and told me to email him my questions, either all at once or one at a time over the course of a couple weeks.

Now I guess is the time for me to write out my list. I don't feel great about it. At this point, I've read enough similar experiences to guess where it's going to go. But at the same time I feel a sort of sense of duty to leave no stone unturned, to let him make a good-faith effort to answer, and to see if perhaps I can demonstrate there really aren't good answers available for the problems I have. At the very least, he will remember that someone who ticked all the boxes of faithful membership, was open and honest with him, and who was willing to do what he asked still did not receive a spiritual witness of the truth claims of the church. To be honest, I was impressed so far with his willingness to let me put forward the hard questions.

The downside is that it will take a lot of time and energy for both of us. I have some hope, though, that greater understanding will be the ultimate result. He hasn't accused me of secretly harboring terrible sins, at least. He really doesn't know what to think right now. Which is good, I think?

“Send Me Your Questions”