Book Review: From Third World to First, by Lee Kuan Yew

The story of the man who built Singapore

Note: This book review was initially published to reddit as a four-part series. The first part can be found here or here. I have lightly edited it and consolidated it for republishing here.

Intro

We believed in socialism, in fair shares for all. Later, we learned that personal motivation and personal rewards were essential for a productive economy. However, because people are unequal in their abilities, if performance and rewards are determined by the marketplace, there will be a few big winners, many medium winners, and a considerable number of losers. That would make for social tensions because a society's sense of fairness is offended. ...Our difficulty was to strike the right balance. (95)1

What happens when you give an honest, capable person absolute power?

In From Third World to First, Lee Kuan Yew, in characteristically blunt style, does his best to answer that question.

Lee Kuan Yew's politics—and by extension Singapore's, because he really did define the country—are often, I feel, mischaracterized. In We Sail Tonight For Singapore, for example, Scott Alexander characterizes it as reactionary. This is agreeable to the American left, because it's run so differently to Western liberal ideals, and agreeable to reactionaries, because Singapore is preternaturally successful by almost any metric you care to use.

The only problem is that the claim reflects almost nothing about how Lee Kuan Yew actually ran the country or who he was.

I get the impression it's a mistake to frame Singapore alongside a partisan political axis at all, because the second you do, half of what the country does will seem bizarre. Lee, personally, is open about his party's aim to claim the middle ground, opposed by "only the extreme left and right." (111) With that in mind, what works best to predict Lee's choices? In his telling, he is guided continually by a sort of ruthless pragmatism. Will a policy increase the standard of living in the country? Will it make the citizens more self-sufficient, more capable, or safer? Ultimately, does it work? Oh, and does it make everybody furious?

Great, do that.

From Third World to First is the single most compelling political work I've read, and I'd like to capture as much of Lee's style and ideology as possible. He divides the book (or at least the half I'm reviewing; I'll leave his thoughts on world affairs alone because there's so much to cover as is) into sections based on specific policy problems and how he approached them. I'll focus my attention on a few:

Citizen welfare & development

Free speech & free press

Approach to political opposition

Handling of racial & cultural tensions

At the end, I will link to my notes in full, and those who are interested are welcome to ask for more details. Depending on interest level, I may write a follow-up review of topics I don't have space to cover here. Note especially that LKY spends huge chunks of the book praising the politicians working alongside him and emphasizing their role. Ultimately, though, the decisions for the country flowed through him and so I am comfortable approaching all these as his policies.

LKY's writing is thoroughly readable and often hilarious, so I will quote it extensively throughout.

Part One: Citizen welfare & development

I.

To even out the extreme results of free-market competition, we had to redistribute the national income through subsidies on things that improved the earning power of citizens, such as education. Housing and public health were also obviously desirable. But finding the correct solutions... was not easy. We decided each matter in a pragmatic way, always mindful of possible abuse and waste. If we over-re-distributed by higher taxation, the high performers would cease to strive. (95)

There are two major questions LKY had to answer when it came to developing Singapore. First, how could the country develop a strong economy? Having achieved that, how could they ensure the welfare of all citizens? Or, as he put it, he wanted to leapfrog the region and then create a "First World oasis" (58).

LKY's strategy for the first was simple: provide goods and services "cheaper and better than anyone else, or perish." (56) He was proudly adamant about his country's refusal to beg, describing on every other page how he would go to his citizens and say things like "The world does not owe us a living." (53) or "If we were a soft society then we would already have perished. A soft people will vote for those who promised a soft way out, when in truth there is none. There is nothing Singapore gets for free." (53)

This is one of many areas where he was adamant about rejecting conventional wisdom. In his telling, development economists and other third world leaders of the 60s described multinational corporations as "[neocolonialist] exploiters of cheap land, labor, and raw materials... but... we had a real-life problem to solve and could not afford to be conscribed by any theory or dogma." (58)

So, instead, he threw his country's arms open and said, "Exploit us!" Image was everything. To attract tourism, they invented the merlion symbol and scattered it through the country. Places were renamed. My favorite—"Blakang Mati" (behind death), an island formerly used by a British battalion, was reinvented as "Sentosa" (tranquillity), a tourist resort. (54) To inspire confidence and demonstrate his country's discipline and reliability, LKY focused on planting trees and developing parkland in the center of the city and between the airport, his office, and hotels. For one Hewlett-Packard visit, when an elevator wasn't yet powered to take them to the sixth floor of their planned headquarters, Singaporean officials extended a cable from a nearby building to power it day-of. (62)

In the 70s, as the country's economy stabilized, that confidence manifested in other ways, as with this interaction:

When our... officer asked how much longer we had to maintain protective tariffs for the car assembly plant owned by a local company, the finance director of Mercedes-Benz said brusquely, "Forever," because our workers were not as efficient as Germans. We did not hesitate to remove the tariffs and allow the plant to close down. Soon afterward we also phased out [other protections]. (63)

The whole thing, at least from a distance, follows a pattern of initial tight control, caution, and centralized planning, followed by a slow move towards a freer economy as long as everything seemed to be working. Worried about government starting industries and running them at a loss, LKY insisted that state-run corporations stay in the black or shut down. As they succeeded, they privatized—telecommunications, the port, and public utilities all started within the government and became independent profitable companies over time. (67)

II.

From a Labour Party meeting in June 1966: "Lee Kuan Yew [is] as good a left-wing and democratic socialist as any in this room." (34)

I could go on for a while longer outlining Singapore's growth, and part of me wants to, because the story is fascinating. It's hardly unique, though, just the story of a well-managed economy. Everyone already knows about the growth of Singapore's economy. The work it took is worth noting, but much more compelling for me is what they did with all that new wealth. The United States had a hundred years or more to manage a jump Singapore went through in a couple decades. Growth brings all sorts of questions: How do you shift people to a new way of life? How do you get people invested in their country's success? How do you handle welfare, health care, transport? This is where Singapore excels.

Not without controversy, though, aided and abetted by Lee Kuan Yew himself. As much as I tend to appreciate his approach, his bluntness sometimes gives me pause. Here's a sampling of his thoughts on welfare:

We noted by the 1970s that when governments undertook primary responsibility for the basic duties of the head of a family, the drive in people weakened. Welfare undermined self-reliance. People did not have to work for their families' well-being. The handout became a way of life. The downward spiral was relentless as motivation and productivity went down. People lost the drive to achieve because they paid too much in taxes. They became dependent on the state for their basic needs. (104)

And:

There will always be the irresponsible or the incapable, some 5 percent of our population. They will run through any asset, whether a house or shares. We try hard to make them as independent as possible and not end up in welfare homes. More important, we try to rescue their children from repeating the feckless ways of their parents. We have arranged help but in such a way that only those who have no other choice will seek it. This is the opposite of attitudes in the West, where liberals actively encourage people to demand their entitlements with no sense of shame, causing an explosion of welfare costs. (106)

So—welfare bad. Got it. What's his alternative?

Funding Prosperity

The foundation for his strategy was laid before Singapore left colonial rule: an compulsory 5% pension fund (the CPF) with employers matching 5%. This fund became a major tool to support LKY's value of self-sufficiency. As he says, he "was determined to avoid placing the burden of the present generation's welfare costs onto the next generation" (97). So how did he fund welfare plans?

As Singapore's economy grew year by year, workers' wages went up. As wages rose, knowing that people would "resist any increase in their CPF contribution that would reduce their spendable money", he increased mandatory CPF contribution rates with part, but never all, of that increase. At its peak in 1984, mandatory contribution increased to 25% with full matching. Every working citizen was automatically saving at a 50% rate. This decreased to 40% over time. (97)

Every aspect of citizen welfare becomes easier when every worker has that large a guaranteed savings account.

Following the pattern of initial strictness, followed by expanding rights, the government expanded CPF investment options over time. One illustrative example: when they privatized bus services, they allowed citizens to spend up to S$5,000 to buy initial shares in the new transport company so "profits would go back to the workers, the regular users of public transport" ...and, as LKY adds in the same tone a moment later, to reduce incentive to demand cheap fares and government subsidies. (103)

This strategy repeated when they privatized Singapore Telecom, as they sold shares at half price to all adult citizens, with bonus shares every few years provided people held onto initial shares. Again, LKY describes this desire to redistribute surpluses and provide people a tangible stake in their country's success. He reports that 90% of the workforce owned Singapore Telecom shares. (103)

Neither the CPF fund nor HDB housing, incidentally, can be taken by creditors.

Sense of Ownership

Aside from pensions, LKY's initial major vision for the fund was a way to allow citizens to buy their own houses. He talks a lot about the value of people having a stake in their country, how a "sense of ownership [is] vital for [a] society [with] no deep roots in a common historical experience," (96) the ways home ownership increases civic pride and a sense of belonging. So the government constantly bought land up, built high-rise public "HDB" housing (up to 50 stories!), and then sold apartments to citizens. At its peak, 87% of Singaporeans lived in this public housing.

Some design decisions of HDB housing are worth examining. In some, LKY asked developers "to set aside land... for clean industries which could then tap the large pool of young women and housewives whose children were already schooling" (98). When older housing started decaying, the government created a program to upgrade and refurbish older apartments at the cost of S$58,000 per home, charging owners S$4,500 of that cost (100).

It's easy to get lost in policy details: decisions, reasoning, numbers. What about the humanity behind those policies, though? What was life like on the ground for the farmers and market vendors who abruptly found themselves moving from wooden huts to modern high-rises in the middle of a rapidly developing city? There was exciting progress, yes, but much of the time it was tragic, hilarious, and absurd.

LKY highlights some of these moments. Pig farmers, nudging their pigs up staircases to raise them in high-rise apartments. A family, gating off their kitchen for a dozen chickens and ducks. People walking up long flights of stairs because they were afraid of using elevators, using kerosene instead of electric bulbs, selling miscellaneous goods from ground-floor flats. (99) He grows somber as he talks about resettling older farmers, how even generous compensation money didn't matter next to losing "their pigs, ducks, chickens, fruit trees, and vegetable plots," and how many of the older farmers never really stopped resenting the change. (180)

He's quick to point out other changes, though: In riots in the 1950s and early 60s, he recalls, people joined in, breaking cars, lighting fires, reveling in chaos. Later in the decade, after home ownership started to spread, he mentions seeing people carrying scooters to safety into their HDB apartments. In his words, "I was strengthened in my resolve to give every family solid assets which I was confident they would protect and defend, especially their home."

"I was not wrong." (103)

I laughed when I got to that line, because I'm pretty sure this picture holds pride of place in LKY's mind. He presents this blithe sense of self-assurance throughout the book, with every controversial policy and scornful dismissal.

Health care

Speaking of blithe self-assurance and scornful dismissal, he dismisses the British National Health Service as idealistic but impractical and destined to cause ballooning costs, then takes a shot at the American system with its "wasteful and extravagant diagnostic tests paid for out of insurance." He reports that at least in Singapore, the ideal of free health care clashes with human behavior. Doctors prescribe free antibiotics, patients take them for a few days, don't feel better, and toss them out. Then they go to private doctors, pay, and take the medicine properly. (100)

The first solution was a token 50-cent fee to attend outpatient dispensaries. The full solution, and part of the reason Singapore's per capita health care costs are half the UK's and less than a quarter of the US's, once again went through the CPF pensions: 1% set aside into "Medisave" for health care costs at first, gradually increasing to 6%, capped at S$15,000. "To reinforce family solidarity and responsibility", LKY reports, accounts could be used for immediate family members as well. (101)

That's not to say he wanted no subsidies. At government hospitals, patients chose wards subsidized up to 80%, moving to more comfortable and less subsidized wards as they desire. Medisave funds could be used for private hospital fees in order to compete with government hospitals and pressure them to improve, but not for outpatient clinics or private general practitioners. Why? LKY didn't want to encourage people to see doctors unnecessarily for minor ailments. (102) This constant tinkering and fine-tuning around incentive systems is core to LKY's planning.

From there, Singapore added optional insurance for catastrophic cases, then added a fund from government revenue to provide total waivers for those who lacked Medisave, insurance, and immediate family. Per LKY's reporting, "no one is deprived of essential medical care, we do not have a massive drain on resources, nor long queues waiting for operations." (102)

Pragmatism.

Taxes

So how does this welfare structure reflect in taxes?

Every few pages in The Singapore Story, Lee Kuan Yew makes some grandiose statement about Singapore's successes, and so every few pages I would rush online to see what was exaggerated or cherry-picked and what has faded in the years since LKY's time. The tax structure was the point where this yielded the most fruit—not because of any cherry-picking, but because almost everything has gotten better in the 19 years since LKY wrote his book.

Here are some details on Singapore's tax structure, both as LKY reported and at present, in pursuit of an overall goal to shift from taxing income to taxing consumption:

Top marginal income tax rate decreased from 55 percent in 1965 to 28 percent in 1996 (now 22 percent).

Corporate tax rate of 40 percent reduced to 26 percent (now 17 percent)

No capital gains tax

3% GST (goods and services tax, equivalent to VAT (now 7%)

0.4% import tariff (now duty-free)

Inheritance/estate tax was cut from 60 percent to 5-10 percent in 1984, leading to increased revenue "as the wealthy no longer found it worthwhile to avoid estate duty" (now abolished)

In addition, they collect non-tax revenue from a range of charges, aiming for "partial or total cost recovery for goods and services provided by the state" to "check over-consumption of subsidized public services and reduce distortions in the allocation of resources." (107)

How has this reflected on overall government expenditures?

At the time of LKY's book in 2000, annual budget surpluses had been recorded every year but the 1985-1987 recession. Since then, 2002-2004, 2009, 2015 also recorded deficits, but the government is still running at a comfortable surplus overall.

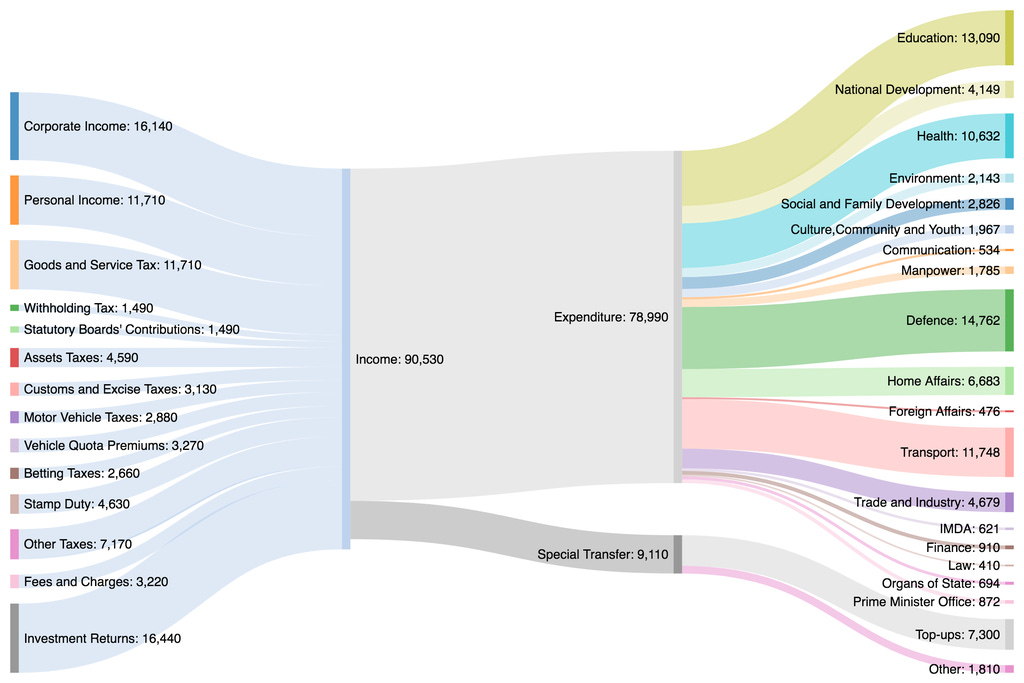

Here's what the budget looked like in 2016.

Ultimately, as LKY points out, his strategy relied heavily on a unique set of circumstances leading to steady growth, but they capitalized on that growth, made long-term decisions early, and set themselves up well for the foreseeable future as a result. I don't share a ton of his skepticism towards Nordic-style welfare states, particularly since they remain comfortable and successful twenty years later, but I'll admit to more than a twinge of envy when I compare Singapore's approach to welfare with that of the US.

Interlude

Having made the claim that Singapore really isn't reactionary, I'm left to defend it after a string of quotes and choices that, if not reactionary, at least seem tailor-made to pick fights with leftist thought. This is one reason I quoted the British Labour Party members at the start of section II. Lee Kuan Yew started the PAP as a socialist party, driven by trade unions, opposed to British colonialism, aligned with British progressives. Again and again throughout the book, you see LKY pause to note potential unintended consequences of a choice, to approach major decisions with caution, and to change his approach when presented with sufficient evidence, but threads of progressive ideals are persistent throughout and essential to his decision-making.

Those threads should become more apparent as I progress through more of the review, fitting naturally with Lee's overall bluntly pragmatic approach. Singapore is unlike any other country in the world, and while nothing done there can copy 1:1 over to different settings, there's a lot worth noticing.

Part Two: You are Free to Agree

Are you a fan of free speech? Are you eager for everyone to have a platform? Are you in favor of an open, unconstrained press?

Lee Kuan Yew isn't, and he's probably poking fun at you.

Free Press

Here are a few of his choicest quotes on Western-style free press:

My early experiences in Singapore and Malaya shaped my views about the claim of the press to be the defender of truth and freedom of speech. The freedom of the press was the freedom of its owners to advance their personal and class interests. (186)

And:

I did not accept that newspaper owners had the right to print whatever they liked. Unlike Singapore's ministers, they and their journalists were not elected. ...I do not subscribe to the Western practice that allows a wealthy press baron to decide what voters should read day after day. (191)

And, when he got into an argument with the US State Department:

The State Department repeated that it did not take sides; it was merely expressing concern because of its "fundamental and long-standing commitment to the principles of a free and unrestricted press"—which meant that "the press is free to publish or not publish what it chooses however irresponsible or biased its actions may seem to be." (192)

All that's pretty straightforward, and clearly goes against the principles of free speech, right? Then you get to the next quote:

We have always banned communist publications; no Western media or media organization has ever protested against this. We have not banned any Western newspaper or journal. Yet they frequently refused us the right of reply when they misreported us. (191)

Here's a question. You're a tiny city-state occupying valuable territory, trying to stay independent. You are watching the cultural revolution sweep across the homeland of three-quarters of your people, and you keep noticing them funding your newspapers. Meanwhile, other superpowers are locked in an all-out ideological struggle with those forces, a struggle that's shaping policy around the whole world. The country's dominant English-language newspaper at the time of gaining independence was "owned by the British and actively promoted their interests." (185)

What's the right level of freedom of press?

Keeping in mind that the book is telling things from LKY's perspective and so naturally seeks to cast his decisions favorably, his position has some nuances that make it easy to be sympathetic. First, there's a different standard for local and foreign media: "We had to tolerate locally owned newspapers that criticized us; we accepted their bona fides, because they had to stay and suffer the consequences of their policies. Not so 'the birds of passage who run [foreign-owned papers].'" (187)

Second, as he mentions above, he didn't ban non-Communist foreign press. Not exactly. Instead, every time a paper refused right of reply for a story he felt was misrepresented or slanted, he just restricted sales licenses to smaller numbers, with an eye towards reducing advertising revenue but not towards outright banning the ideas. This led to occasionally amusing exchanges. In one back-and-forth, after the Asian Wall Street Journal (AWSJ) published an alleged defamatory article and had sales restricted, the AWSJ offered to distribute its journal free to its deprived subscribers to "forego its sales revenue in the spirit of helping Singapore businessmen". Singapore's government agreed, as long as it left out advertisements. The paper backed out, claiming cost issues. Singapore offered to cover half the additional costs. When the paper refused, Singapore gave an official response: "You are not interested in the business community getting information. You want the freedom to make money selling advertisements." (193)

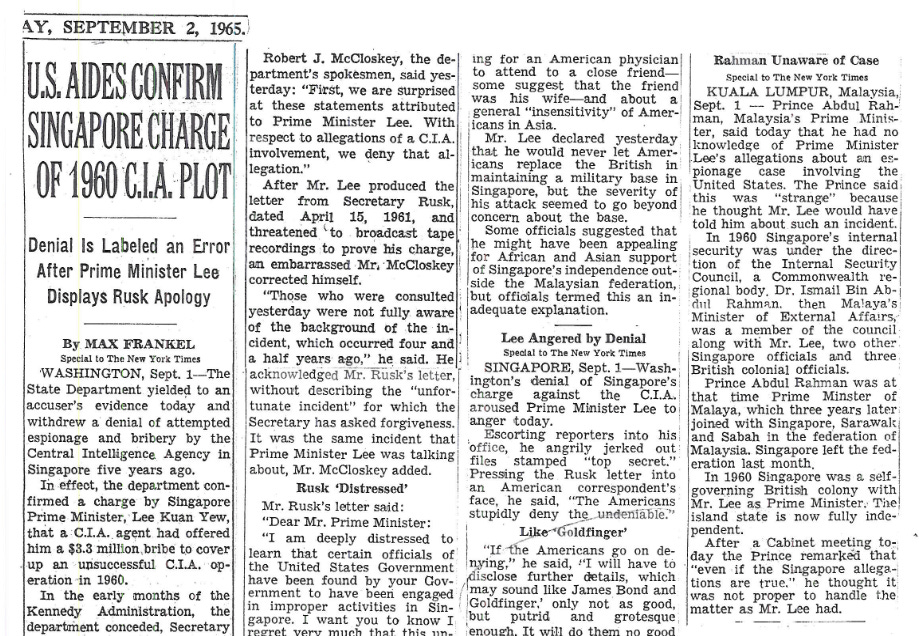

Third, well, it's only paranoia if you're wrong. In addition to facing consistent attempts at covert communist influence, I learned post-reading that Lee Kuan Yew had at least one memorable run-in with the CIA (h/t /r/singapore). In 1960, they offered him $3.3 million to cover up a failed attempt to buy information from Singapore intelligence officials. Lee's response? "The Americans should know the character of the men they are dealing with in Singapore and not get themselves further dragged into calumny. ...You do not buy and sell this Government." Never one to ignore leverage, he requested that instead of covert bribes the US provide public foreign aid. They complied.

Dystopian information lockdown, or prudent defense against foreign influence and misinformation? LKY is convinced, rightly or not, that it is the latter. Read with modern US politics in mind, it's easy to compare it to deplatformings from tech websites, concerns about Russian infiltration of social media, or the controversies around fake news. The context changes, the challenges stay the same.

Free Speech

I frankly have much less sympathy for LKY's eagerness to sue people for libel. It's worth mentioning that Singapore has avoided one obvious concern about relying on courts here: corruption is almost non-existent in Singapore, and deliberately so. We may come back to corruption later, since LKY does spend some time on it. Still, there's something unsettling about the leader of a country keeping a hawk's eye watch for anything that misrepresents him, then turning the power of the courts on the individual or newspaper who went after him.

He talks about a fair number of legal battles with evident satisfaction, about taking this opponent or that who accused him or corruption or lied about him to court, then winning the battles. He anticipates the obvious criticism about this practice, and defends against it:

Had I not sued, these allegations would have gained credence. ...Outrageous statements are disbelieved only because they are vigorously refuted. If I failed to sue, that ould be cited as proof that there was something in it. ...Wrong ideas have to be challenged before they influence public opinion and make for problems. (130-131)

And:

Far from oppressing the opposition or the press that unjustly attacked my reputation, I have put my private and public life under close scrutiny whenever I appeared as a plaintiff in court. Without a clear record, it would have been an unnecessary hazard. Because I did this and also gave the damages awarded to deserving charities, I kept my standing with our people. (131)

Left unspoken, though, is that he's the one who's in charge of this whole system of lawsuits. Vigorous refutation of an idea can happen in writing, in speeches, in any number of official channels. If he wants to keep his public and private life open to scrutiny, he can do so however he chooses. Electing to wage time-consuming and costly legal battles against people who putforward unsavory ideas is hardly the only choice for the most powerful man in a country, and it's a choice that I feel warrants skepticism.

I'm much more fond of his response to a London Times reporter who made accusations he disputed (emphases mine):

I wrote to invite Levin to a live television debate in London on his allegations. Levin's editor replied that no television station would be interested. I had taken the precaution of first writing to the chairman of the BBC, my friend Marmaduke Hussey, who had agreed to provide half an hour and a neutral moderator. When I informed the London Times of this offer, the editor on Levin's behalf backed off, arguing that my response should be in the same medium in which Levin had attacked me, namely the Times. I wrote to regret Levin's unwillingness to confront me. When the Times refused to publish my letter, I bought a half-page advertisement in the British daily, the Independent. Interviewed on the BBC World Service, I said, "Where I come from, if an accuser is not prepared to face the person he has attacked, there is nothing more to be said."

Levin has not written about Singapore or me since. (196)

There's something delightful about the image of a politician going up to a reporter and saying, in effect, "Heard you were talking smack. Debate me, you coward."

Another instance shows up, by the way, in which it's hard to make assumptions about Singapore. Given LKY's desire for control over media messaging, you might expect some sort of overreaction to the internet. Instead, his message comes with characteristic bluntness: "Countries that try to block the use of IT will lose." (196)

On nanny states

One last topic remains to be covered here. From banning everything from drugs to tobacco advertising to chewing gum to eating durian in public spaces, Singapore has inevitably faced accusations of being a "nanny state."

LKY has this to say on the subject:

Foreign correspondents in Singapore have no big scandals of corruption or grave wrongdoings to report. Instead they reported on the fervor and frequency of these "do good" campaigns, ridiculing Singapore as a "nanny state." They laughed at us. I was confident we would have the last laugh. We would have been a grosser, ruder, cruder society had we not made these efforts to persuade our people to change their ways. We did not measure up as a cultivated, civilized society and were not ashamed to set about trying to become one in the shortest time possible. First, we educated and exhorted our people. After we had persuaded and won over a majority, we legislated to punish the willful minority. It has made Singapore a more pleasant place to live in. If this is a "nanny state," I am proud to have fostered one. (183)

To rephrase: "Yep, we're a nanny state. Works great. Any questions?"

I'll repeat my above explanation of LKY's approach: Will a policy make people more self-sufficient, more capable, or safer? Ultimately, does it work? Oh, and does it make everybody furious?

Great, do that.

On a world scale, I think I would be uncomfortable with this sort of standard. I believe in the importance of creating robust societies where a wide range of ideas can thrive, and this sort of deliberately limited culture doesn't really provide that. But part of creating robust systems is questioning assumptions and experimenting with dramatically different approaches. I'm from Utah. I grew up in a similarly self-restricting and proud "nanny state". While it wasn't right for me in the end, for a lot of people I'm close with, those unambiguous strict standards work really, really well in a way that "eh, just do what makes you happy" doesn't. A single city of five and a half million people seems to me just about the right size to run that sort of experiment.

Interlude Two

While reading the book and looking a bit into Singapore, I came across a few pieces of info that don't fit naturally into a review but deserve at least a moment's attention. One is the matter of Singapore's airport.

You might recall from my first review a brief mention of Lee Kuan Yew's focus on first impressions so people would "know that Singaporeans were competent, disciplined, and reliable... without a word being said" (62). Singapore's Changi airport takes that to its natural conclusion. He was determined to make Singapore a transport hub of the region and decided to write off their investments in an older airport to perfect Changi in a number of details. After seeing Boston's Logan Airport, for example, he reported being "impressed that the noise footprint of planes landing and taking off was over water" (203) and adjusting plans accordingly. In the end, they spent six years and $1.5 billion constructing the airport in a sort of anti-Brandenburg approach.

And (h/t elsewhere on reddit): The airport is wild. Features include: multi-story slides, a massive playground of climbing nets, an indoor playground and waterfall, hedge mazes and canopy bridges, and, well, just about everything else. Oh, and it has airplanes too. It's been ranked pretty consistently as the best airport in the world.

Part Three: Race, Language, and Uncomfortable Questions

Here's a tricky governing problem for you.

Imagine your country had historically encouraged a minority group to segregate into lower income communities with poor living conditions.

Picture, too, that that minority group had historically underperformed in school compared to others.

Say that your country had faced large-scale riots in the 1960s over concerns about perceived government discrimination and oppression.

To spice things up, let's add that they're the country's indigenous people, and that they speak a different language and practice a different faith than everybody else in the country.

...and that initially, they formed the vast majority of the military and the police force, and the majority in your much larger neighbor country. It's hardly going to mirror other countries exactly, after all.(12)

How do you ensure justice for them and for all citizens?

Singapore has its advantages over other countries, true. It's... what was the quote?... "a single city with a beautiful natural harbor right smack in the middle of a fantastic chokepoint in one of the biggest trade routes in the world." 1

But demographically, it's complicated, to say the least. 75 percent of Singaporeans are Chinese. Of that majority, about a third speak English at home, half speak Mandarin, and the rest speak other dialects. They split between Buddhist, Taoist, Christian, and irreligious. 15 percent are Malay, and almost all of them speak Malay (90%) and practice Islam (99%). Another 7 percent are Indian, and they tend to speak Tamil and practice Hinduism, but there's a long tail of other languages and faiths. That's after 50 years of coming together. To pull one example of the past, in 1957, 97 percent of Chinese Singaporeans spoke a language other than English or Mandarin at home.

What LKY did to ensure his country's economic prosperity was remarkable and prescient, but where he truly cements his legacy and confounds expectation, in my eyes, is the way in which he handled the most sensitive issues around race and language.

The Malaise of the Malays

Let's return to the governing problem introduced at the start of this section, the complex situation of Malays in Singapore. Assuming absolute power, how do you get a nation to stop self-segregating, particularly when a minority group you're not a part of is concentrated in a slum?

A month after independence, LKY promised the 60000 Malays living in shanty huts in one area that "in 10 years all their shacks would be demolished and [the area] would be another and a better 'Queenstown,'" then their most modern housing. (207) Rather than approach them himself and create a sheer top-down push around difficult decisions like replacing mosques, he spoke privately with Malay members of parliament (MPs), got buy-in from the Muslim governing body of Singapore (MUIS) to allow an old wooden mosque to be demolished, and set up a building fund for the MUIS to build replacement mosques. Compensate homeowners, give them priority in new housing estates, take the 40 families who refuse to vacate to court... done.

...and then, when he realized that people would naturally re-segregate, he got the support of minority parliament members to create race-based quota ceilings for government apartments so that people would have no choice but to intermingle.

You should be used to the pattern by now. Every solution on the table, go for the most direct and efficient way to achieve a goal, push forward regardless of decorum. That part's predictable. What I found more compelling was his emphasis on working with and through minority government members each time he worked with minority communities.

Which raises the question: how could he guarantee he would have minority representatives, given that citizens would naturally prefer MPs who empathized with them, spoke their language, so forth? What's the most Singapore way to solve that particular problem?

That's right, snap your fingers and merge constituencies into clusters of three or four, require candidates to run as groups, and mandate that each group include at least one minority candidate. After all, LKY reminds readers with what sounds like a shrug, "To end up with a Parliament without Malay, Indian, and other minority MPs would be damaging. We had to change the rules." (210) To quote online commenter /u/lunaranus: "For an American politician this kind of change would be the legislative achievement of a lifetime. For LKY it was Tuesday."

So that's segregation taken care of. Is there another, more controversial issue to bring into focus?

"To have people believe all children were equal, whatever their race, and that equal opportunities would allow all to qualify for a place in a university, must lead to discontent. The less successful would believe that the government was not treating them equally." (210)

I'll let that quote speak for itself.

Again, though, the interesting part isn't the blunt diagnosis of problems. The interesting part is the solution. He privately gathered Malay community leaders together, provided them the test results, and promised them the government's full support as they sought solutions. Every time a Malay-focused issue came up, he emphasizes, he would consult with his Malay colleagues and get their input and buy-in. This approach upset some of his senior ministers, one of whom he mentions "was a total multiracialist [who] saw my plan not as a pragmatic acceptance of realities, but as backsliding." (211)

I'll keep his own wording for his response to the concerns:

While I shared [the minister's] ideal of a completely color-blind policy, I had to face reality and produce results. From experience, we knew that Chinese or Indian officials could not reach out to Malay parents and students in the way their own community leaders did. The respect these leaders enjoyed and their sincere interest in the welfare of the less successful persuaded parents and children to make the effort. Paid bureaucrats could never have the same commitment, zest, and rapport to move parents and their children. ...On such personal-emotional issues involving ethnic and family pride, only leaders of the wider ethnic family can reach out to the parents and their children. (211)

In the end, the Malay leaders formed a government-assisted council to help struggling students with extra tutoring in evenings, and the government provided funding for them and a group of Muslims who wanted to approach the same objective more independently of government. Indians and Chinese community leaders followed with their own similar associations not long after.

As of 2005, Singaporean Malays have shrunk, but not closed the gap with other Singaporeans, and leapfrogged most non-Singaporean students in educational outcomes.

LKY's handling of these issues is one reason I see it as futile to place him on a traditional US-style left-right axis when looking at his decision-making. His approach blends traditional, family values and blunt realism easy to associate with the right with a determination to work with affected minorities and concern for their welfare that pattern-matches more clearly to the left. That mixture of familiarity and foreignness in his approach, and that tension between traditional and progressive values, is one reason this work was so refreshing for me, coming from a US background.

When he discusses Chinese schools and the transition to English education, he reveals more about his personal life than anywhere else, and some of that mix begins to make sense.

Chinese schools, English language

Lee Kuan Yew describes his education, in English-language schools and then overseas in England, in mixed terms: "deculturalized," textbooks and teachers "totally unrelated to the world [he] lived in," "a sense of loss at having been educated in a stepmother tongue," "not formally tutored in [his] own Asian culture... not belonging to British culture either, lost between two cultures." (145)

He talks about his decision to send his children to Chinese schools to give them a firmer footing in their own culture, and talks about his appreciation of the "vitality, dynamism, discipline, and social and political commitment" in those schools. English-language schools, on the other hand, "dismayed" him with the "apathy, self-centeredness, and lack of self-confidence" in their students (149). Later, he speaks with regret about Western media and tourism eroding "traditional moral values" of Singapore's students, about how "the values of America's consumer society were permeating Singapore faster... because of our education in the English language." (153)

But they had a common culture to build, an English-centric business world to look towards, and a need for unity in their armed forces and elsewhere. So English, as LKY tells it, was needed as a common language, his concerns and those of his countrypeople aside. In Chinese, Malay, and Tamil schools, he mandated English courses. In English schools, he mandated the teaching of mother tongues. Malay and Indian parents shifted quickly to English schools, but Chinese parents were less satisfied and a hard core of resistance formed.

In this issue, again, some of the reasons for LKY's success as Singapore's leader become clear. At times, he opted for simple authoritarian solutions: arresting newspaper managers for glamorizing communism, deporting Malaysian leaders of student demonstrations, removing a union leader who "instigated his fellow students to use Chinese instead of English in their examination papers." (148) But then he talks about how his English education allowed Malays and Indians to see him as Singaporean rather than a "Chinese chauvinist," and how his "intense efforts to master both Mandarin and the Hokkien dialect," and the experience of his children in Chinese-speaking schools, let him relate to and be accepted by the Chinese-educated (149), and it becomes clearer that something more than authoritarianism was at play.

That sensitivity became critical when issues with Chinese-language education came to a head. Students in the Chinese language Nantah University—the flagship symbol of Chinese language, culture, and education, fundraised and built by the Chinese community—struggled to find jobs. He describes the decision to switch the university and most Chinese schools to English in conflicted tones, emphasizing that he could speak with authority and "[maintain] the political strength to make those changes" primarily because he had sent his children to Chinese schools.

It bears repeating that Lee Kuan Yew is pretty dismissive of a lot of Western traits. He cites Japan approvingly as a culture able to "absorb American influence and remain basically Japanese," with their youth "more hardworking and committed to the greater good of their society than Europeans or Americans" (154). In an effort to preserve the best in Chinese schools and retain that sort of cultural influence, he set aside the top nine Chinese schools as selective institutions, admitting only the top 10 percent of students.

So—did LKY successfully lead his country to a new common language while preserving culture? Sort of. Even now, the policy has had mixed impact, and LKY sounds more torn here than in any other part of the work:

Bilingualism in English and Malay, Chinese, or Tamil is a heavy load for our children. The three mother tongues are completely unrelated to English. But if we were monolingual in our mother tongues, we would not make a living. Becoming monolingual in English would have been a setback. We would have lost our cultural identity, that quiet confidence about ourselves and our place in the world. ...

Hence, in spite of the criticism from many quarters that our people have mastered neither language, it is our best way forward. (155)

Later in life, LKY expressed regrets about his insistence on bilingualism: "Nobody can master two languages at the same level. If (you think) you can, you’re deceiving yourself."

I had a Singaporean friend a while back who sometimes joked that you could tell she was Singaporean because she spoke bad English and bad Chinese. I wasn't in a place to judge the truth of that, at the time speaking no Chinese myself, but there was a hint of sadness behind the joke that stuck with me and comes to mind with LKY's eventual hesitance around the policy. Since then, I've expended a lot of effort on learning Chinese myself, and the same distance between the languages is clear and discouraging. It's a tough problem, and I don't know that there was an ideal answer in a society as multicultural and multilingual as Singapore's. I get the sense from this section of Singapore, at least in LKY's eyes, sometimes reflecting his own torn feelings, between languages and between cultures.

Still, Singapore made it through the shift and has developed a strong culture and its own satisfying twist on English, so it would be unfair to mark the policy as a failure overall. To find a true failed policy, we need to turn to a different topic.

The limits of tweaking culture

A paraphrasing of Lee Kuan Yew to the Malay community: I am not one of you, but I will listen to you. I will ensure you have equal opportunity to the rest of our citizens. I will push to allow you proportional representation. Every step of the way, I will listen to you and your leaders when deciding on policies that affect you. When I need you to make changes in sensitive areas, I won't enforce it top-down and bureaucratically, I will approach your trusted family and community leaders and ask them to take charge.

The same, for the Chinese community: I recognize your fears about your culture being lost if your language fades. I lost it myself, educated in foreign schools and a foreign language, and have since fought to regain it. It is a priority for my children. I love the best parts of our culture and want to preserve them. Understand that the only reason I am asking you to make a difficult transition away from it is because that is what our country needs in the world as it stands.

It's in light of those two cautious, thoughtful, empathetic approaches that this third story frustrates me so much.

Singapore, more than any other country in the world, is facing a birthrate crisis. Current numbers place its fertility rate at 1.14, lowest in the world. It's a pressing issue, tricky and multifaceted, one reflective of trends around the world. It's also deeply sensitive, tied into people's sense of self-determination and autonomy, their most personal goals, and a whole lot else. Further complicating it is the uncomfortable reality that education and birthrate typically have an inverse correlation. As of Singapore's 1980 census, "the tertiary- [and secondary-]educated had [a birthrate of] 1.6, the primary-educated, 2.3, and the unschooled, 4.4" (140).

Lee Kuan Yew noticed the issue, because he noticed every issue. He also noticed that women tend to prefer "marrying up", men "marrying down", because of course he did, how a lot of the country's graduate women were remaining single, and how that could impact his nation's future talent. So, how did a leader who relied so much on his ability to inspire trust react to the challenge?

I decided to shock the young men out of their stupid, old-fashioned, and damaging prejudices. (137)

That's right, by telling everyone they're stupid and trying to strong-arm a change:

On the night of 14 August 1983, I dropped a bombshell in my annual National Day Rally address. Live on both our television channels, with maximum viewership, I said it was stupid for our graduate men to choose less-educated and less-intelligent wives if they wanted their children to do as well as they had done. (135)

In the comment thread of my first review, commenter /u/Greenei pointed out that LKY sounds "like a nerdy, rationalist, technocratic dictator. Disregarding society's irrational feelings, speaking the truth plainly, and changing your views with new evidence." I agree. In this instance, though, it's easy to see in him the caricatured side of that image: a stubborn insistence that everyone be convinced by a waterfall of pure facts, eagerness to phrase those facts in the bluntest possible way, and deliberately apathetic to the role emotion plays in changing minds.

Genetic influences on intelligence remain just as controversial as they were in LKY's day. To avoid getting caught in those weeds, I'll proceed assuming he was entirely correct. Given his track record, it's not a stretch. Even granting that, even granting the difficulty of the problem, I can't help but feel his approach was dead wrong.

First: Provide preferential school selection for children of graduate mothers who have at least three kids. He mentioned expecting nongraduate mothers to be angry at being discriminated against. Instead, graduate mothers rose up against the change, saying things like:

"I am deeply insulted by the suggestion that some miserable financial incentives will make me jump into bed with the first attractive man I meet and proceed to produce a highly talented child for the sake of Singapore's future." (137)

Next: Establish a government matchmaking system to "facilitate socializing between men and women graduates" (138).

Finally: Support both of the above with repeated reminders of statistical analyses, genetic research, assertions of cultural prejudices, and round condemnation of misleading but politically correct Western writers.

The results were predictable. Western media, of course, rose up against him. His party, famously leading an effective one-party state, lost 12 percent of the vote in the next year's election. Half his cabinet condemned his decisions. Only those who already saw the same issues he did—the "hard-headed realist[s]" in his cabinet (140), along with writer R. H. Herrnstein—really stood by him. Eventually, he gave up on the policies and rested his hopes on immigration instead.

It's easy to look at the whole saga and conclude that he was pushing against impossible trends that not even the most prescient could avoid, ready with a bluntness and willingness to speak hard truths as a lonely, brave Cassandra. That certainly seems to be his portrayal of his approach. But I can't help but feel that, in this case, all he accomplished was poisoning the well for every future attempt to address the real problems he identified. While it's impossible to say whether another approach would have succeeded, this one emphatically did not.

Conclusion

One of LKY's greatest strengths that comes through as I read the book is his relentless determination to follow the facts where they lead. Just as important, though, is leading others to follow those facts. In some incredibly sensitive situations, like when he helped his Malay citizens and led the charge towards English as a common language, he did a fantastic job of this—not just by leading with his head, but by demonstrating good faith and doing what it took to build genuine trust with others.

But no leader is perfect, and it's as instructive to learn from failures as from successes. When people feel misunderstood, insulted, or attacked, it doesn't matter how sure you are of the facts. They will withdraw and entrench. LKY admits to his own impatience here: "Intellectually, I agreed... that overcoming this cultural lag would be a slow adjustment process, but emotionally I could not accept that we could not jolt the men out of their prejudices sooner." (141)

As someone with my own tendencies in the same direction, I feel inclined to translate: I knew I was making a mistake, but they were wrong!

Interlude Three

One of my favorite small moments from the book comes when LKY discusses the process of greening Singapore. As he points out, "Singapore's size forced us to work, play, and reside in the same small place, and this made it necessary to preserve a clean and gracious environment for rich and poor alike." (181) From their independence in the early 60s, they made planting trees and cultivating greenery a priority. When LKY noticed some planted trees were dying off, he presented the quintessentially Singaporean solution of a government department "dedicated to the care of trees after they had been planted" (175).

The best bit, though, comes when he mentions how a friendly competition started among Southeast Asia in the 1970s. Malaysia, Indonesia, Thailand, and the Philippines all got involved. In LKY's telling:

No other project has brought richer rewards to the region. Our neighbors have tried to out-green and out-bloom each other. Greening was positive competition that benefitted everyone—it was good for morale, for tourism, and for investors. It was immensely better that we competed to be the greenest and cleanest in Asia. I can think of many areas where competition could be harmful, even deadly. (177)

Greening is the most cost-effective project I have launched. (178)

As for the results? Judge for yourself.

Part Four: The Pathway to Power

So far, my review has mostly left out one massive elephant in the room. Lee Kuan Yew was Prime Minister of Singapore from 1959 to 1990. When he stepped down from office, he went straight into a close advisory role, sticking around the government in some official capacity until 2011. How was he in power so long? What was his approach to opposition and to political disagreements, beyond lawsuits? Where did he fall on the scale of democratically elected leader to dictator?

As with every other topic, LKY is pretty candid about this all. The best place to start, though, is likely not with the overt political battles. Instead, I'll focus where he focused early: the unions.

Unions

This section will dive into the weeds a bit more than most of my writing. It's for a good cause, I promise.

In the late 1950s and early 1960s, Singapore had, to put it bluntly, a union problem. Between July 1961 and September 1962, the country faced 153 strikes. In LKY's telling, most unions were under communist control, and all "had turned combative," having learned from British trade unions "all the bad habits and practices of how to squeeze employers for more pay and benefits regardless of the consequences to the company." (83)

So Lee Kuan Yew, ardent reactionary that he was, tore unions down, stripped protections and regulations away, and ushered in a new and gloriously productive era of unfettered capitalism.

Those of you who've followed this review so far won't be surprised to hear that's just about exactly not what happened. This chapter came early in the book, and it's where LKY's personal story started becoming really, really interesting to me. Why? Well, it's when he casually mentioned his political experience before becoming Prime Minister:

He was a legal advisor and negotiator, fighting on behalf of trade and student unions (and, unrelated to our current focus but fun to note, moonlighting as a free speech defender when a university socialist club published a "seditious" article). You might remember the quote from part one of my review, when a Labour party leader emphasized how committed a socialist LKY was. What did that mean when he took charge and faced trouble with unions? As he was urging unions to abandon some destructive practices, he was facing down against policies he was responsible for, protections he had fought for when his country's workers were being exploited, but that were damaging his country enough he regretted his decision.

He cites as an example triple pay on public holidays, which "led to cleansing workers deliberately allowing garbage to accumulate before public holidays to ensure that they would have to work on these holidays." (84) Elsewhere, he cites the trouble of employers investing in expensive machinery to minimize need for workers, leading to "a small group of privileged unionized workers getting high pay and a growing band of underpaid and underemployed workers." (84) With these and related concerns in mind, he went in 1966 to a meeting of union leaders from around Asia, asked them not to "kill the goose whose golden eggs [they] needed," (84) and got to work encouraging changes like pay for performance over time on job.

Union leaders objected. He pushed forward, but "took care to meet the union leaders privately to explain [his] worries... [in] off-the-record meetings [to] make them understand why [he] had to get a new framework in place." (85) That actually worked for most. Step one, then: come up with a careful plan, explain it in private, draw support. Step two?

Well, it's Singapore. One "irrational and ignorant" (85) union leader over cleaners and other daily-paid workers delivered an ultimatum asking for a pay raise and then called for some 2400 cleaning workers to strike. LKY ordered the dispute to arbitration to make the strike unlawful. When the union went on strike anyway, the police arrested the leader and 14 others. The union registrar issued notices of potential deregistration to the union. The ministry of health told the workers they had sacked themselves and could reapply for employment the next day.

And, the next day, ninety percent of the workers applied for reemployment, LKY had the support of the public, and union culture started to shift to a give-and-take. He went first to the union leaders, then to employers, urging cooperation and fairness, and emphasized that "unless [they] made a U-turn from strikes and violence toward stability and economic growth, [they] would perish" (88).

On to step three. In 1968, Singapore passed comprehensive laws covering leave, bonuses, and other points of contention. In 1969, they had their first full year without strikes. In 1972, they established a council between union members, employers, and government to determine annual wage increases. LKY requested his colleague Devan Nair return to Singapore to lead the union congress, and under his lead union delegates decided to focus their attention on setting up co-ops in taxis, supermarkets, insurance, and afterwards a strikingly broad array of industries.

The whole thing, at least in LKY's telling, was a spiraling and mutually beneficial arrangement. As union leaders got experience directing co-ops, they gained greater appreciation for the role of good management. To help "reduce the feeling that workers belonged to a lower order," (91) the government subsidized union land purchases for clubs, resorts, and other facilities. To nurture talent, the unions set up a labor college per LKY's urging, and he encouraged talented students returning from overseas to work in the unions and strengthen them.

Why do I emphasize this in so much detail? Primarily to underscore this quote:

Strict laws and tough talk alone could not have achieved this. It was our overall policy that convinced our workers and union leaders... but ultimately it was the trust and confidence they had in me, gained over long years of association, that helped transform industrial relations from one of militancy and confrontation to cooperation and partnership. (88)

And later, this reminder of his guiding ethos as he discusses the checks and balances of unions:

The key to peace and harmony in society is a sense of fair play, that everyone has a share in the fruits of our progress. (93)

As in tensions around race and language, as he approached the unions Lee Kuan Yew balanced strict, hard policy with the reassurance that he understood his people and wanted to help them—and, we Westerners don't fail to note, a side of authoritarianism. Reason and careful negotiation for most, coordinated and overwhelming force when negotiation breaks down, and pragmatic, prosperity-centered policy in the aftermath. It's a pattern you can see again and again. This pattern is one major reason to focus on the unions. The other is that both LKY and his greatest early rivals had their roots in that movement.

Communists

I:

Disclaimer: I am entirely unqualified to provide a thorough, balanced account of Lee Kuan Yew's rise and the controversies in Singapore's early history. My intent here is to present the story largely as LKY writes it. For other sides of the story, consider this BBC article, Wikipedia on the opposition Barisan Sosialis, biographies of those LKY names as communists in his book: 1 2 3 4 5, a couple of reddit threads 1 2 3 plus a journal article (Scihub) if you're feeling particularly ambitious. tl;dr: There was definitely strong communist influence in Singapore; some LKY accuses of being communists vehemently deny it and likely shouldn't be considered communist; even these non-communist leftists were heavily influenced by Mao and the Cultural Revolution.

Here's an understatement for you: Lee Kuan Yew was not fond of communism. Understandable, given that China went through the full sweep of the Cultural Revolution as he rose into influence. Throughout his book, he speaks of communists with a fascinating mix of fear and respect.

In his telling, the early history of post-colonial Singapore is framed almost entirely as a struggle between his People's Action Party (PAP) and communists. In the 1950s, there was a sort of uneasy alliance between LKY's moderate wing of the PAP, a left wing headed by Lim Ching Siong, and the underground communist organizations in place in Singapore, all eager for independence from Britain. As soon as the PAP became the majority party in 1959, though, that alliance splintered. By 1961, the PAP expelled its left wing (13 of its 39 members), which became the Barisan Sosialis. That's where the real fun began.

If you ask the Barisan, they were non-communist leftists. If you ask LKY, they were a front organization for communism. He takes evident delight throughout a chapter of his book outlining the rise and collapse of their party. The government was contested through the 60s, in and out of an attempted union with Malaysia. In 1968, though, the Barisan declared Singaporean elections illegitimate and refused to participate, electing instead to take inspiration from Mao and call the people of Singapore to "smash all the trammels that bind them and rush forward along the road to liberation" (Cheng 226). The people did not smash the trammels. Instead, the Barisan left the PAP virtually unopposed, granting it uncontested control of the government, and faded quickly from relevance. LKY mentions that it was this "costly mistake... [that] gave the PAP unchallenged dominance of Parliament for the next 30 years." (110)

From there, as he tells it, communist influence shifted into terrorist attacks and bombings during the 70s and a relentless "hardcore following of some 20 to 30 percent of the electorate" (111), as Maoist organization worked throughout the Chinese-speaking part of Singapore. LKY rushes through this, preferring to more specifically outline the falls of several of their leaders (and a few overt communists). Each spent years to decades in jail or exile, only permitted to reenter Singapore upon cutting links with the party and disclosing all past activity.

That may be too passive. Put more bluntly: LKY tossed them in jail, with British approval but without trial, and makes no secret of having done so. He is extremely open about his willingness to take whatever measures necessary to stop communism. His description of their conflicts sounds, simply, like an all-out war:

We learned not to give hostages to our adversaries or they would have destroyed us. (112)

And:

Could we have defeated them if we had allowed them habeas corpus and abjured the powers of detention without trial? I doubt it. Nobody dared speak out against them, let alone in open court. (113)

And:

They were formidable opponents. We had to be as resolute and unyielding in this contest of wills. ...Their ability to penetrate an organization with a cadre of influential activists and take control of it was fearsome. (114)

And:

Despite ruthless methods where the ends justified the means, the communists failed, but not before destroying many who stood up against them, and others who after joining them decided that their cause was mistaken. (119)

From 1963 to 1989, Singapore detained some 690 people, often holding them for years without trial. They required any political actors to affiliate with parties explicitly to "force [communists] out into the open and make them easy to monitor" (115). LKY spoke of the impossibility of progress while "communists retained their baleful influence" (108). In short, he did everything he possibly could to stamp communism and Maoist influence out of Singapore. Your level of comfort with these decisions will likely depend either on your opinion of communism or your commitment to free expression. Charitably, LKY saw the horrors of the Cultural Revolution and determined to stop it within his sphere. Uncharitably, he saw an opportunity to destroy his opposition and take absolute power, and he took it.

For me, though, far more compelling than his opposition to communism was his commitment to learn from their methods.

II:

See, even while LKY lays out his fight against communism, you hear fascinating hints of respect in his descriptions of them. He describes how the PAP, when they took office, were "sickened by the greed, corruption, and decadence of many Asian leaders" (157), and how a similar disgust led Chinese-school students in Singapore to support communism. They "saw the communists as exemplars of dedication, sacrifice, and selflessness, the revolutionary virtues displayed in the spartan lives of the Chinese communist leaders." (157) Later, when describing his conviction that "candidates must not need large sums of money to get elected" (164), he again cites communists, pointing out that they didn't use money to win votes.

Much earlier, when discussing his own need for security, he mentions that while "threats from racial fanatics [were] unpredictable... the communists were rational and calculating and would see no benefit in [attacking his family]" (5). And return to his description of communists failing. He mentions "the skillful and tough methods of the unyielding communists... were unforgettable lessons in political infighting." (112) When dismissively comparing a later opponent to them, he mentions they were "formidable adversaries... serious men, committed to their cause." (125)

Why am I harping so much on this point? Well, much has been made of Singapore's near–one-party system. From a two-party system like the USA, or the multi-party systems in much of the rest of the developed world, it's hard to picture a setting where one party wins every election, time in and time out, without assuming corruption. Lee Kuan Yew provides an explanation for it, and as with many of his lessons in the groundwork of politics, it comes straight from his encounters with the communists. This next quote is pretty long, but I'm sharing it in full because it strikes me as one of the most important insights LKY provides, one that is relevant for every ideological movement:

We had learned from our toughest adversaries, the communists. Present-day opposition leaders go on walkabouts to decide where they will do well, based on the way people respond to them at hawker centers, coffee shops, food courts, and supermarkets, and whether people accept the pamphlets they hand out. I have never believed this. From many unhappy encounters with my communist opponents, I learned that while overall sentiment and mood do matter, the crucial factors are institutional and organizational networks to muster support. When we went into communist-dominated areas, we found ourselves frozen out. Key players in a constituency, including union leaders and officials of retailers' and hawkers' associations, and clan and alumni organizations, would all have been brought into a network by communist activists and made to feel part of a winning team. We could make little headway against them however hard we tried during elections. The only way we could counter their grip of the ground was to work on that same ground for years between elections.

I emphasize this quote so strongly because it speaks directly to my own frustrations with ideologies. Anyone who steps away from an ideology because they believe something in it is untrue will almost inevitably notice, and grow frustrated, with just how many people brush off those same untruths. Lee Kuan Yew doesn't present a new concept here, but he articulates it clearly and directly: Absolute truth is mostly disconnected from success. Organized ideas thrive; scattered ideas fail. People need rallying flags. They lunge for teams. Truth matters a bit, yes, but much more importantly, what are you doing for people? Good organization beats a good idea every time.

If you want the best ideas to win, organize for them.

Did Lee Kuan Yew have good policy ideas? From my angle, yes. There's nothing remarkable about that, though. Plenty of people have those ideas. What truly sets him apart as a figure worth studying, in my eyes, is not just the quality of his ideas but the way he combines them with a depth of understanding of institutions and power.

And in part, he had his deepest adversaries, the communists, to thank for it.

So how did he do it? Why, 60 years later, does the PAP still hold 83 of 89 seats in Singapore's parliament?

Staying in power

I.

After winning all the seats, I set out to widen our support in order to straddle as broad a middle ground as possible. I intended to leave the opposition only the extreme left and right. We had to be careful not to abuse the absolute power we had been given. I was sure that if we remained honest and kept faith with the people, we would be able to carry them with us, however tough and unpalatable our policies. (111)

Our critics believed we stayed in power because we have been hard on our opponents. This is simplistic. If we had betrayed the people's trust, we would have been rejected. (121)

What do you do, as a new political party struggling to gain a foothold, then an abruptly dominant force, to get the trust of everyday citizens? How do you organize?

One tool LKY used was the People's Association (PA). He intended the association to be a hub, not just of political activity, but of useful community resources in general: literacy classes, technology instruction, cooking courses, so forth. To aid in this, he invited influential community members from "clan associations, chambers of commerce, recreational clubs, and arts, leisure, and social activity groups" (122), and set up more than a hundred community centers throughout Singapore.

Next came the "welcoming" and "goodwill" committees—activists in local communities called up to discuss things like road improvements, street lights, and drains on the one hand, delicate race relations on the other. Successful and eager members of these turned into leadership for community centers and "citizens' consultative committees" who received funds to provide public works, welfare grants, and scholarships.

None of these institutions were explicitly partisan. They were aimed at the maintenance tasks of community life, the uncontroversial but useful background structures. LKY mentions that many wanted to avoid active association with political parties, largely as a holdover from colonial times and threats of retribution. These institutions allowed the government to work with "elders who were respected in their own communities" (123), making it easier to reach out to people at all levels. Recall the time LKY worked with Malaysian community leaders to create plans for education—this structure was the means by which he managed it.

Add government housing to this (with its own "residents' committees", and you begin to see the strength of this soft power: layers and layers of semi-political community figures, helping people day-to-day, working alongside the People's Action Party even when not directly affiliated with them. As LKY puts it, "Opposition leaders on walkabouts go through well-tended PAP ground." (123) He credits his own political strength to public speaking skill, which he took advantage of in an annual unscripted address in Malay, Hokkien Chinese, Mandarin, and English, and in rallies around the country.

Voting another party into power, then, would mean in part needing to figure out a whole new system of organization at all levels. The PAP wasn't shy about using this sort of advantage, either. LKY rather proudly mentions one election where they promised priority public housing upgrades for constituencies that voted more strongly for the PAP, then follows it up with one of those lines that could only come from him:

This was criticized by American liberals as unfair, as if pork barrel politics did not exist elsewhere.

Honest. To a fault.

Viable opposition came in a few districts, eventually. That, too, he aimed to turn to his advantage. He spends time on one opponent voted into one precinct in 1981, a "sound and fury" (124) demagogue who took mostly opportunistic stands and who "probably kept better opponents out" (125). Realizing that some MPs hadn't ever faced serious opposition, LKY says, he "decided he was useful as a sparring partner" (125). There's a great "fifty Stalins" moment, too, when he mentions a "shrewder" opponent who apparently reflected the population better by saying the PAP was doing well, but "could do better and should listen more to criticism." (125) In response, the PAP was respectful, aiming to encourage "nonsubversive opposition."

II.

As much as my American instincts lead me to look at this all and want to talk about how controlling and oppressive the idea of this sort of single-party rule is, I find it difficult to do so without proving too much. The US, after all, has two major political parties and a bunch of nearly inconsequential competitors, choked out by organization and history and election rules. On Singapore's scale, one-party leadership isn't unusual here. My home state of Utah has voted for the Republican party since 1968. Chicago, only a little smaller than Singapore, has been under one party since 1927. Organizing, providing services to encourage people to keep them around, criticizing opposition, and promising to help those who support them sounds like, well, every political party on the planet. And when measuring corruption, Singapore compares rather favorably to the US—and, well, almost anywhere else.

Take one element LKY focuses on: money and special interests in politics. Singapore made voting compulsory in 1959 and has enforced strict spending limits in elections throughout the PAP's time as majority party. LKY mentions that neither communists, nor the PAP, nor opposing parties have ever spent much money to win elections. In 2015, the PAP spent $5.3 million between 89 general election candidates. Sticking with Chicago as a point of comparison, their most recent mayoral elections saw a single candidate raise more.

LKY is dismissive as well of the idea of anchoring ministerial salaries low. He explains: "Singapore will remain clean and honest only if honest and able men are willing to fight elections and assume office. They must be paid a wage commensurate with that men of their ability and integrity are earning for managing a big corporation or a sucessful legal or other professional practice." (166) He points out with distaste the "revolving door" system in the US, where high-paid private sector workers are appointed to posts by the president, then return to the private sector with "enhanced value". Part of avoiding this was the decision to remove most perks and allowances and provide benefits as lump sums. The rest was a gradual process: freezing ministerial wages until 1970, then raising them from S$2,500 to S$4,500 monthly while his own was "fixed at S$3,500 to remind the public service that some restraint was still necessary." (168) In 1995, after periodically raising wages, Singapore fixed salaries of senior public officials at two-thirds of their private sector equivalents.

Despite this relative high pay, he shares several stories of times he persuaded people to take salary cuts for government work: a bank GM making S$950,000 per year who he persuaded to become minister of state at a third that salary; a chief justice who went from making S$2 million a year as a banker to S$300,000 in the court, who according to LKY "accepted [the] offer out of a sense of duty" (218).

III.

Most interesting, for me, is how LKY closes his chapter on maintaining control in the political system:

Will the political system that my colleagues and I developed work more or less unchanged for another generation? I doubt it. Technology and globalization are changing the way people work and live. ...Will the PAP continue to dominate Singapore's politics? How big a challenge will a democratic opposition pose in the future? This will depend on how PAP leaders respond to changes in the needs and aspirations of a better-educated people, and to their desire for greater participation in decisions that shape their lives. Singapore's options are not that numerous that there will be unbridgeable differences between differing political views in working out solutions to our problems. (134)

I get the sense that in aiming to maintain power, as in all else, LKY was a pragmatist. He did not aim to set up a dynasty that lasted generations or seek to obtain glory at all costs. He found a system that suited his country's needs at the time and put it in place, anticipating that Singapore would change as it needed to. Make no mistake: he wielded near-absolute power, and he knew it. But he did not abuse it.

Conclusion

One last question remains to be answered, not about Lee Kuan Yew, but about this review:

Why have I spent 12,000 words and the better part of a month poring over the policy of a tiny country of five million, and a leader who hasn't formally been in charge since 1990? What's my agenda?

Put simply, I think it's worth paying attention to. Not the specifics of the policy, so much: Singapore is a unique country, and solutions adapted to its culture and position are unlikely to translate perfectly to other environments. More than that, I am fascinated by the way LKY's approach cleaves at right angles the modern Western political landscape. Three points stood out from Lee Kuan Yew's achievement in Singapore:

It was not inevitable. It's easy to frame things like this in retrospect as certainties of history, but I honestly think that's the wrong view of Singapore. It came close to collapsing in the 60s, and while it used its unique advantages as a port city to the full, LKY took it where he did with a series of careful, rational decisions. Policy specifics like welfare and health care, measured approaches to racial and political tensions, and the others detailed through the book could have gone a myriad of other ways under different leadership, resulting in a very different city even if it still developed. His political power came because he organized and planned for it.