Note: I originally posted this essay on Reddit on Pioneer Day of 2020. Now that the day has rolled around again, I reproduce it in full here (one day late, but better than not at all).

July 24 is a holiday you've never heard of, but one that meant quite a bit to me growing up. As with most things that fit that description, it's recognized only in Utah: Pioneer Day, a celebration of the men and women who rode in covered wagons or dragged handcarts across a thousand miles or so to build a new society in Utah.

That, more than anything else, is the founding myth I grew up identifying with. It dovetailed so neatly with the parts of the American founding myth we chose to emphasize, too, the message of a persecuted religious minority coming to a new land to build a system where they were free to worship as they pleased.

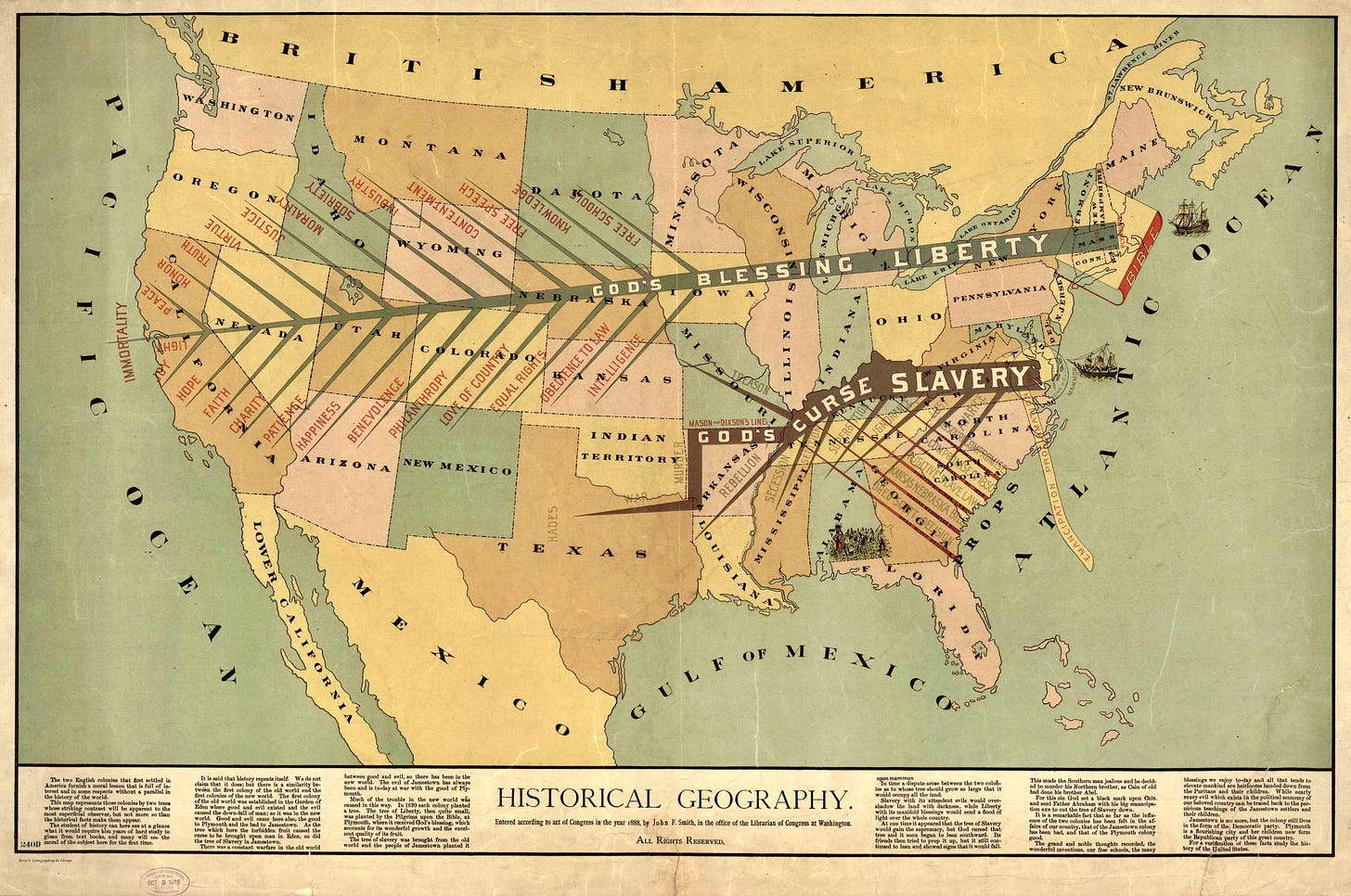

This 1888 map encapsulates the broader history I was used to picturing, but unlike the more distant pilgrims, the pioneers were mine. My family had been in Utah for six generations. I could go through the old books my parents and grandparents had preserved and read their stories, told firsthand. We learned about them in church, and I even had a year-long course covering church history to replace one of my high school classes. Every few years, our church would get together and organize a pioneer trek, where we would dress as pioneers, gather into "families", and pull handcarts for a few days.

It was my heritage, I felt it strongly, and I was deeply proud of it.

Ah, when life was simple, and I wasn't a broken link in the chain of my generations.

Anyway, today is a day of celebration, not of griping. So I'd like to share two stories—one a subset of the other—that we would always remember and celebrate as inspirational and faith-kindling. I will explore them in part through the trusting eyes of my youth, in part through my current, more tired eyes, and I'll see what pops out of both. If you want a soundtrack for this post, you could do worse than Come, Come, Ye Saints:

This will be perhaps a bit sappy, as my posts go, but that's fine. It's a holiday.

First is the story of the Martin Handcart Company.

The Willie and Martin Handcart Companies

When Mormons first traveled across the plains, they went in relative ease, with teams of oxen or horses to pull wagons as part of larger wagon trains. You know, the full Oregon Trail experience. Some ninety percent of the people who went west took this approach. The rest? Well, the church ran out of money and they still wanted to come over, so they became their own oxen, loading up everything they could carry on carts and dragging their belongings and their kids all the way to Deseret. (Per the Book of Mormon, it means "honeybee").

Okay, I can't resist a bit of a digression here. Did you know Mormons once created their own alphabet? It's true. They wanted a more phonetic approach than the standard English alphabet to make it easier for immigrants to learn the language. Didn't catch on, but it's pretty fun to look at.

Anyway, the first three handcart companies that went west did surprisingly well, with "only" around a 3-5% fatality rate. You had the standard range of axle breakdowns, illness, and low rations, but by and large, everyone made it through. Emboldened by these successes, two other companies got together in 1856, sailing across from England that May and running headlong into what would become disaster compounding on disaster. It started with miscommunications with the church's agents in Iowa City, which meant delays in throwing together carts, and flowed into more delays as they tried to repair poorly built carts. It was mid-August by the time they were ready to leave, a start late enough in the year that they worried they would run into trouble with winter weather on the trail.

Or at least Levi Savage, who had previously made a similar trip marching from Iowa to California as a member of the Mormon Battalion, was worried, and told the rest it was foolish and dangerous to leave so late. The rest? Eh, divine intervention will protect us, right? What could go wrong?

Everything. The answer is everything. Here's a description from the rescue party sent to meet them a few months later, as they were hunkering down in Wyoming:

It is not of much use for me to attempt to give a description of the situation of these people, for this you will learn from [others]; but you can imagine between five and six hundred men, women and children, worn down by drawing hand carts through snow and mud; fainting by the wayside; falling, chilled by the cold; children crying, their limbs stiffened by cold, their feet bleeding and some of them bare to snow and frost. The sight is almost too much for the stoutest of us; but we go on doing all we can, not doubting nor despairing.

First, they had traveled to Fort Laramie, Wyoming, arriving in October and expecting to be restocked with provisions and finding nothing. Then they tossed some "extra" clothing and blankets to lighten the load. In mid-October, a blizzard struck. They ran out of food and had to slaughter their cattle. River crossings became freezing death-traps. Hypothermia and frostbite spread through the camps. People began dying in droves. Finally, rescue parties arrived from Utah and saved them from further disaster.

A folk Mormon story talks about how three eighteen-year-old boys from the rescue company carried nearly everyone from the Martin Handcart Company across the Sweetwater River in Wyoming, all dying from side effects of the exposure in later years. This story took several liberties with the truth, which is a shame, because a rescue company dragging a group of frost-bitten, starving pioneers across a river is dramatic enough without the embellishment.

In the end, 68 of the 404 members of the Willie Handcart company died on the trail, as did at least 145 of the 576 in the Martin Company.

One of the many ways this was weaved into a "faith-promoting story" was a line etched into Mormon folklore:

... did you ever hear a survivor of that company utter a word of criticism? Not one of that company ever apostatized or left the church because everyone of us came through with the absolute knowledge that God lives for we became acquainted with him in our extremities.

Immense sacrifice leading to certain testimony of God's existence, carried as a memento throughout their lives? Powerful stuff.

Shame my own family story told me differently.

The Story of Jane Brice

Every Utah Mormon has at least one pioneer story. It might be my bias talking, but I've always thought my family's was the best. Let me introduce you to Jane Brice, a ten-year-old member of the Martin Handcart Company who traveled to Utah with her father, mother, and older brother. Some of it might be exaggerated, but to the extent it was, the exaggerations are hers: she dictated the story personally in 1916. The factual outline is easily verifiable.

Her family was converted in Wales and sailed over as part of the Martin Handcart Company in 1856. You already know the outline of the Martin Handcart Company's journey. After the first snowstorm, her mother fell ill. Later, at one of the Sweetwater River crossings, her mother died and the company buried her. I'll leave it to Jane's account for some of the details of the journey afterwards:

Our progress became so slow that we sometimes traveled only a half a mile a day. One night it thundered and lightening so terribly that we were forced to camp and to go to bed without anything to eat. It was now November and so cold that nearly everyone had frozen feet. One man had both feet frozen so badly that he had to have them amputated. When I took my shoes off one night after a very cold day’s travel, my feet were black with blisters, and in the left ankle was a big hole which had been caused by the frozen condition of my feet. (The hole in her ankle remained the rest of her life—a reminder of the ordeal on the Wyoming plains!) One toe was frozen so badly that I thought it would surely come off. My feet were so terribly swollen, that I could not wear my shoes, so I had to wrap them in old rags and sacks in order to walk at all. To keep my hands from freezing, I would clasp them at the back of my neck and with the aid of my thick black hair, prevented them from freezing.

At least it was a happy ending when they reached Salt Lake City at the end of November, right? Every member of the company remained faithful and true and lived happily ever after.

Not so much:

When on the thirtieth of November, my father saw the barren winter valley that Salt Lake City was in 1856, he said, “And this is Zion—the Zion we have suffered and lost so much to reach—Why this is nothing but a God-forsaken desert! I’m going back to England with the first company that travels East.”

Whoops. Two years later, her father gathered her and her brother up to head back to England and give up on the whole affair. That's where the story would end in most cases: a sad, pointless trip that led to the death of his wife over a religion he no longer believed. But Jane wasn't keen on returning. Instead, when the wagon train was ready to leave and go east, she ran off to hide in a woodpile. As she tells it, she sat there sobbing, knowing she would never see her father again. He looked around for her, then when he couldn't find her, asked a friend to take care of her and left. Her reasoning for staying, in her own words:

"Because Mother said this is where we should be and she died trying to get here. I know this is where I should stay!”

Her first-person account ends there, but the transcriber notes details of her later life: how the family she was adopted by turned out to be a bit nasty and worked her to the bone, how another man adopted her a few years later, how she never heard from her father again and received her first letter from her brother ten years later, how she later became the first polygamous wife of one of the settlers, and a bunch of fond recollections from the transcriber, her granddaughter.

Reflections

When I was growing up, this was one of my favorite stories. I asked after it, and reread it, and retold it often. The faith of a ten-year-old child who knew her mother had died to get her somewhere, then stayed there despite her father's abandonment and built a life for herself, is quite the moving story for her descendents who share her faith. It's so perfectly inspiring. I remember, when I doubted my faith, being able to cling to it and think that whatever my own concerns, her sacrifices and her faith must mean something. The pioneer story was my founding myth, and Jane Brice my personal connection to that legacy.

And now here I am, having walked away from all that.

What do you do, when reality creeps in to a beautifully formed myth, and you view a set of actions that seemed so inspiring in the new light of disbelief? Here is the reality: My ancestors traveled from all over America and northwestern Europe to Utah, throwing away their old lives (and for some, their lives, full stop) in pursuit of a dream woven by a charismatic, grandiose story-teller who caught them up in his fantasy. Jane Brice's mother did not need to die. The pioneers did not need to walk to Utah. Mormons did not have a divine calling to sweep in, start wars with the people who already lived in the territory they claimed, and colonize Utah.

But here, too, is the reality: Jane Brice was sincere in her belief, and she made sacrifices for it far beyond what we're used to in this day and age. The pioneers as a whole were operating from the most compelling information they had access to at the time, and they built institutions and cities and a society that persists through today. There's a certain dark humor to her father being correct about Mormonism, but she did only what he and her mother had taught her was right, and he abandoned his child rather than stay a moment longer in Utah. And in the end, my family has by and large lived happy, fulfilling, good lives in Utah, building on what she did.

The founding myth, in its pure form, is untenable with what I now know. Even with that, though, there is something genuine to respect here. For one who believes, as I do, that there is value to building positive mythologies, it's not a stretch to construct a new founding myth of the same story, one which I can still hope to live up to: a willingness to work and sacrifice and build for what you believe in, even when that means choosing a different path than your family and your culture before you. Proceed from the best information you have, and then work for it. To get a bit cheesy: A ten-year-old girl sailed across the ocean, walked a thousand miles, and later hid in a woodpile and watched her father abandon her in order to do what she perceived as right. What's my excuse?

Happy Pioneer Day.

Thanks, this was fantastic. I haven't heard my family talk about our Pioneer stories, but later I looked at the church's family history search website that will tell you if you're related to anyone famous. Turns out I have a few ancestors who were in the Willie-Martin handcart company. But, for whatever reason, they stayed in Winter Quarters and didn't continue onto the fateful leg of that journey.

As someone who's left I've also had conflicting feelings on the legacy of my dedicated pioneer ancestors. Perhaps this is self-congratulatory, but I was really ALL IN and leaving was so incredibly hard for me. I had many times I just wanted God to take me via lightning strike on a hike or getting hit by a car on a bike ride just so I didn't have to follow my conscience out of the church. I got through it, I see many, many good things in it and my wife's a believer but the untruth of it all and the bad was too much for me. Anyway, the self-congratulatory part is that I feel like, in a SMALL sense, I had to have a bit of the courage that my ancestors probably needed to JOIN the church via my LEAVING it (the only one in my family to do so). And it feels like, in a sense, that's honoring those pioneer ancestors.

I'm new here and this post is fantastic. I've been with my ex-Mormon gay husband for 30 years (more on that later). Anyhow, as a Colorado resident I've driven between (Fort) Laramie and Denver many times. If only those handcart zealots had called a time out and turned left and marched south for a week to Denver most would have survived the winter. It's two different worlds. My family dares not take the Wyoming route to visit grampa in Utah during the winter. The white outs and blizzards are too much for a 2020 SUV. God help those folks on foot. The numbers speak for themselves.