In Defense of the New College Takeover

A missive from the desk of Blocked and Reported Chief of Staff TracingWoodgrains, in which I disagree with Blocked and Reported

Intro: “We should have our Chief of Staff, TracingWoodgrains, look into this controversy”

Last week, the podcast Blocked and Reported—that is to say, my workplace—ran an episode focused in part on the recent news that Ron DeSantis has appointed six conservatives to the board of ultra-progressive Florida liberal arts college New College as part of what Chris Rufo describes as a plan to “reconquer public institutions all over the United States.” Katie Herzog and Jesse Singal—that is to say, my employers—were harshly critical of the move. In a bit where they were laughing about the absurdity of bloggers having chiefs of staff, they jokingly invited me to look into this controversy while inadvertently promoting me to Chief of Staff over at the podcast.

My bosses, alongside other writers and thinkers I respect such as Cathy Young, Jonathan Haidt, and Steven Pinker, harshly panned DeSantis’s move as an illiberal political stunt likely to do much more harm than good. This puts me in a bit of an awkward position: I find myself intrigued by what’s going on at New College, even a bit optimistic.

To explain why, I intend to respond to three specific critiques my bosses make of the move in their podcast episode: that there are plenty of non-woke public universities in Florida and there was no reason to target the most progressive one, that building something new would have been much better than aiming to take over an existing institution built by others, and that the answer to bias one direction is not bias in another. Feel free to listen to the episode if you haven’t, but my intent is for this response to stand on its own.

”There’s no shortage of public universities in Florida that, I promise you, are not woke” -Jesse

Of all statements in the episode, this is the one that caught my ear most immediately, particularly when paired with a quip from Katie later on: “This podcast might be the last company in America that doesn’t have a DEI department.” While Katie and Jesse have some disagreements on this question, it was a central enough part of the argument against the move that it’s worth examining in some depth.

“Woke” is a thorny word to define, more of a sliding scale of feeling than a binary yes or no. Still, I find myself skeptical of the idea that any public universities in Florida can truly be considered “not woke”. It’s worth diving into the data to understand why. To provide a baseline, we ought to establish the political leanings of faculty and administration at universities. Bear with me, since this part will unavoidably be a bit heavy on graphs and statistics.

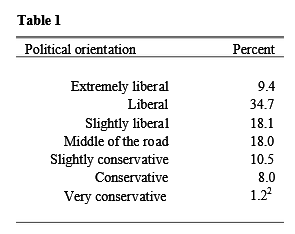

While I have emphatic quibbles with the standard presentation of the 2006 Politics of the American Professoriate survey, which unreasonably classifies a number of self-identified liberal professors who have unambiguously liberal politics as moderates, it remains the most recent highly cited full-scale survey of politics among college professors. It found that some 62% of professors self-identified as some form of liberal, 18% as middle-of-the-road, and 20% as conservative:

The divide is much more dramatic in the social sciences and humanities, where ratios of liberal to conservative professors exceed 10 to one per their reckoning:

In addition, community colleges tend to have slightly more balanced ratios, while liberal arts colleges rival humanities departments in their imbalance:

Per a 2018 survey of top liberal arts colleges, 40% have a grand total of zero Republican professors, while the overall ratio of Democrats to Republicans is 12 to one and the ratios in many of their departments skew towards the unbelievable. Their anthropology and communications departments have no conservative faculty to speak of:

While there has always been a skew, the imbalance has only grown, as documented by Heterodox Academy:

Now, that’s only professors. What about administrators, who have the opportunity to set culture and policy throughout the university rather than simply in classrooms? There, the skew is even more dramatic than that of professors. For university administrators, a 2018 Inside Higher Ed piece and New York Times article provide an idea:

Two-thirds of administrators self-identify as liberal, with 40 percent of that liberal pool stating that they are far left. A quarter of them call themselves middle of the road, while only 5 percent say they are on the right. That makes for a liberal-to-conservative ratio of 12 to one.

In the Southeast, this is amplified, with a 16 to one ratio of liberal to conservative administrators. When compared to to overall occupation data from the General Social Survey, it becomes apparent that university administrators nationwide, in red and blue states alike, are among the furthest-left professionals in the country.

Is Florida an outlier in this regard? Not as far as I can tell. When looking at presidential campaign donations from 2020, close to 89% of donations from Florida university faculty went to Democrats—around what the above numbers would predict. Data on individual university politics can be a bit harder to come by, but school research website Niche does collect self-reported stats from student bodies, providing at least an initial look at the specific public universities in Florida. The full list of self-reported campus politics at Florida public universities is available here. (Niche lacks data on the politics within Florida’s community and state colleges.) Per Niche, the most moderate public university in Florida appears to be the University of West Florida (UWF), with a diverse range of self-reported views:

Federal campaign donations from UWF were a bit more balanced than the state trend, but not much: close to 83% to Democrats compared to 17% to Republicans. Its college of education has a full-time Diversity, Equity, Inclusion & Belonging committee. The university seems to have recently taken down its pages on equity & diversity and identity-based organizations, but had them as late as January 2022. Its undergraduate catalog makes it clear, among other things, that every undergraduate student needs to take a “multicultural course”, some of which sound delightfully weird (“Ritual use of human remains”) and others of which sound potentially interesting but rather overtly “woke” (“Gender and sexuality in Latin America from Colonization to Today”). The overall picture of the university is one whose professors follow the near-universal trend of being overwhelmingly liberal or leftist, particularly in humanities departments, and one that is trying to balance DEI goals with a hostile state administration. Specific data on the politics of its administrators is unavailable, but it would have to be an extraordinary outlier not to have a similar trend to other universities in its region there.

Does all of that make it “woke”? Certainly not when compared to New College, which is unambiguously the most progressive public university in Florida by any measure I can find. I have no personal experience with the university and can only see so much from a distance, so I will not overstep the available information. I can, however, provide a few thoughts on the dynamics in play.

As my bosses and many other “heterodox” liberals, class-first leftists, and others in the rag-tag band of the “non-woke left” repeatedly demonstrate, you can be on the political left without being “woke”. More, as many principled progressives regularly demonstrate, you can support initiatives towards diversity and other progressive goals without leaning full-tilt into every culture war issue. To establish that academia, in virtually every public institution, is dominated by liberals and leftists is not to establish that every individual or every institution is “woke”.

What it does mean, however, is that the political debates that play out within those spheres look very different to the debates that play out in the country writ large. Conservative views are almost unheard of among particularly administrators and humanities departments, those whose work most often intersects with campus politics. In other words, even at a university like UWF, arguments about policy are most likely to play out between moderates and leftists, with liberal and progressive assumptions embedded as part of the shared fabric. As Samuel J. Abrams puts it in the New York Times, “it appears that a fairly liberal student body is being taught by a very liberal professoriate — and socialized by an incredibly liberal group of administrators.”

Outside of places like private religious institutions, this dynamic is almost unavoidable. Not many students in conservative states attend universities as progressive as New College, but no student, choosing a public university in Florida, has an option where the politics of professors or administrators look anything at all like the politics of Florida writ large.

“They’re taking over something that other people built and transforming it into their own image” -Katie

In their episode, Katie and Jesse stress repeatedly that part of the cause for outrage about this mission shift is the desire to transform an existing institution rather than creating a new one. Like them, I prefer when people aim to build something new rather than co-opting something others value. There is unmistakable political gamesmanship in the decision to take Florida’s most progressive public university and fill its board with conservatives. But I cannot help but feel they underestimate some mitigating factors.

Most immediately: New College has not been owned by the people who built it since 1975. It was founded in 1960 as a private college for academically talented students, with some brilliant math and science talents, such as Fields Medal winner William Thurston, coming through its doors in those early years. It never achieved financial stability, though, and was deep in debt by the time the state bought it out in 1975. That’s the last time those who built it can truly claim control over it—from the moment it agreed to become a public institution, it took on the responsibility to serve public needs in exchange for public taxpayer funding.

With that in mind, the university has transformed in a number of ways over the years. While researching this article, I had the opportunity to speak with Tina Trent, a conservative writer who graduated New College in the 1980s and describes herself as “probably the only person who chose between [applying to] West Point and New College.” Despite political differences, she described her memories of the school fondly, with a number of professors she describes as leftists who taught well and were cautious about bringing their politics into the classroom, the opportunity to cobble together her own Great Books program and delve into studies of the classics, and, well, let’s just say not so much ecstasy on campus that a determined student couldn’t avoid it.

Her impression is that it has undergone both a political shift and an intellectual decline since then, becoming much more overtly radical and less intellectually curious, consumed by identity politics, riding the coattails of a reputation squandered away some time ago. She emphasizes that she wants to see the college succeed in much the same way it did in the past, and—having worked and spoken with a number of the incoming board members—she believes they are by and large serious about seeing it succeed as a liberal arts college in line with its tradition, not a clone of Hillsdale.

I do not claim these new trustees would have fit comfortably into some “old New College”, or that one atypical graduate speaks for all students of her time. What I will confidently claim is that New College has seen a number of shifts over the years, and American politics itself has shifted, such that it is hard for me to be persuaded that its current form is an idealized expression of its original founding in a way that the new trustees’ goals for it could never be.

More to the point, New College has not been targeted for an overhaul in a moment of apparent flourishing. As Chris Rufo mentions in his recent remarks to New College faculty, 67% of first-year New College students were in the top 10% of their high school graduating classes in 1993, down to only 21% now. In 2017, lawmakers funded a substantial growth plan, with the mandate to increase the school’s enrollment from 875 students to 1200 by 2022. Its numbers have instead continued in gradual decline, with a current student population of a little over 700 (up from 632 in fall 2021). It lags behind other Florida public universities in other measures as well, from state cost per degree to employment outcomes of recent graduates.

Building a liberal arts college from the ground up is an expensive, long process in the best of circumstances. As the wave of controversy and mockery around the recent announcement of University of Austin indicated, those challenges are intensified when the aims of the school run against progressive trends—while people like Katie and Jesse would be inclined to cut DeSantis more slack for building something new, many progressives criticizing his decision would be no more enthusiastic about the prospect than they are now. When the existing public liberal arts college in a state already struggles to meet enrollment goals, to secure the political will for a wholly new one is a gargantuan task, particularly since the great majority of liberal arts colleges are privately run. That New College is public at all is the result of unique circumstances.

Given all of this, I cannot help but feel that if a project like this was to be attempted at all, New College was the obvious—perhaps the only—location at which to attempt it. That doesn’t make it fair for existing students, faculty, and staff to be dragged into the center of a political firestorm they neither asked for nor wanted. It’s a tough spot to be in and they have every right to be angry, particularly if DeSantis’s plan goes poorly. Ultimately, though, the institution took on a duty not just to its own students but to the public as a whole when it agreed to be bought out by the state and accept taxpayer funding. As I’ll cover in the next section, I find it not only plausible but likely that a change of tone will enable the college to better serve the people of Florida.

“I just don’t think that the answer to bias is a different kind of bias” -Katie

Many people I respect worry about the idea of one institutional bias being replaced by another sort of institutional bias in universities, and embrace the idea that every university should be a joyous hodgepodge of intellectual curiosity with no loyalty, implicit or explicit, to any one creed. This stance, more or less, is held by all those I cite in my intro as critics of this move: my employers, Young, Pinker, Haidt, and other principled and careful thinkers whose stances I take seriously.

I like and respect their position. Is it too impertinent, though, to say they might be wrong?

Before you crucify me, allow me to introduce another set of thinkers I respect:

First is Bryan Caplan, anarcho-capitalist firebrand with a habit of writing compelling, provocative books founded on rock-solid research, whether he’s arguing for fully open borders, mass defunding of higher education, or providing selfish reasons to have more kids. While his hardline libertarianism often strikes me as idealistic or absurd, almost everything he writes challenges me productively and refines my own thinking when I engage with it.

Next are Tyler Cowen and Alex Tabarrok, authors of the wildly popular economics blog Marginal Revolution. Cowen is one of the best interviewers I know of, delving deep into the work of anyone he brings onto his show and aiming both to treat them seriously and to challenge them in his interviews. Both are wildly intellectually curious, pursuing and presenting an eclectic and fascinating range of ideas for the rest of us to chew on.

The last is Robin Hanson, perhaps (said with love) the most autistic of all prominent online writers, who digs into controversial, niche, and often clever ideas with a combination of bluntness and openness that is often equal parts unnerving and valuable. He’s notable not only for his own writing, but for being one of the clearest pregenitors of the online rationalist subculture, writing extensively alongside Eliezer Yudkowsky and laying the groundwork for later thinkers like Scott Alexander, the writer who inspired much of my own intellectual growth.

Those of you who have heard of these men before already likely know what they have in common: they are all professors of economics at George Mason University. This is not a coincidence. Rather, it is the direct result of a conscious choice by George Mason, more than 50 years ago, to zig where other universities zagged, snapping up brilliant free-market economists while their ideas were unpopular in the broader academic market. Fittingly for an economics department, they found and exploited an niche that was undervalued by academia writ large, and were rewarded with a string of brilliant economists, including Nobel Prize winners, and a culture of contrarianism and intellectual curiosity that persists to the present.

The existence of the GMU economics department is a boon to academic and intellectual culture, and has provided serious benefits to me personally, even though I have never attended and most likely will never attend George Mason University, even though I stubbornly and resolutely reject many tenets of the libertarianism of so many of its finest thinkers. It did not spring up by chance. It sprang up out of a conscious, ideologically influenced decision to provide an alternative to the culture embraced by the great majority of universities around it.

In short, universities do not exist in isolation. Jonathan Haidt is absolutely correct about the value of viewpoint diversity in academia. Nobody, sincere or not, well-meaning or not, is free of bias. Nor should people be free of bias—or, in other words, they ought to have clear values. Much more important is to be aware of and explicit about their biases, and to open their work to examination by those with contrary biases. I’ve written before about the value of wrong opinions. If you more-or-less agree with something, it’s easy to brush over shared assumptions and nod along without close examination. Only those motivated to disagree are likely to put in the time and effort to give any intellectual work the serious critique it deserves.

What applies to individuals applies to institutions. Every institution has values: some implicit, some explicit. Every university department, and every university, evolves an overarching culture. When I dream of diversity in academia, I do not dream of a diversity that sees every university aiming to achieve a perfect 50/50 balance of people who fall on the left or the right of the American political spectrum. I do not dream of a diversity in which every economics department offers the same mix of Keynsian, Chicago, and Austrian economics. I dream of diversity between institutions: one in which George Mason economists argue with Harvard critical race theorists, where Chicago Law and Berkeley Law hash out serious disagreements, where to attend one university means to be immersed in its particular culture, with a range of cultures on offer between different universities that is as wide as productively possible.

This feels obvious and pressing in education, the domain I feel strongest about. It’s not as simple as progressive versus conservative in that domain—it rarely is. But schools of education are subject to a range of fads, struggling to adopt the lessons of cognitive science. The most well-publicized example recently has been the question of “The Reading Wars”, a fierce dispute between phonics and whole-language approaches. Other debates and forgotten episodes include “discovery learning” versus direct instruction, the spread of “learning styles” even as its evidence base crumbled, and the school district that threw unimaginable money at education problems with minimal effect. To dive into all of these properly would deserve an article of its own, but each question interacts with ideology in sometimes subtle ways, and our best instincts can lead us astray in a domain where what works is often, maddeningly, what feels worst. The field has been dominated like few others by progressives with progressive instincts, and many of its missteps are in precisely the places where those instincts lead intuition astray.

Right now, the most serious shortage I see in the broader culture of academia is that of serious traditionalist conservative intellectuals and universities. Liberals are well-represented. Libertarians make their showing, and not a half-bad one at that. Heaven knows there are plenty of Marxists. But conservatives have fled the Academy and the Academy has fled conservatives. In the social sciences and humanities—the domains I find most compelling—serious conservative thought is almost wholly absent, and with that absence comes real loss, especially for those who disagree with conservatism. Hiring conservative professors in overwhelmingly liberal humanities departments is part of the solution, but another serious part—and a responsibility that can only fall on conservatives themselves—is the cultivation of more intellectually serious humanities and social sciences departments, alongside liberal arts colleges, with sincere commitments to presenting conservative thought.

By this, I do not mean they should abandon academic rigor, a devotion to truth-seeking, or other core principles of academia. George Mason University has not abandoned them by any measure. Nor do I expect New College to do so. It bears mentioning here that, whatever Rufo’s bluster, the board members are not nearly so in charge of setting the agenda as he likes to imply. Their role is not to set curricula or reading lists, but to fundraise and attract people to the university. Not only that, interviews with other board members indicate much less bombast and dogmatism than Rufo suggests. Incoming New College board members like Matthew Spalding and Mark Baeurlein have sterling academic credentials and are pushing not for some sort of restrictive conservative monoculture, but (to quote Spalding) for “teaching the liberal arts in an academically serious way as the center of its course of study” where students “may assert and defend any argument [they] conceive, as long as [they] do so in a way that is civil, academic, and conducive to thought and deliberation”. Bauerlein, for his part, emphasizes the value of pluralism and the role of the existing student body and tenured faculty in setting bounds on what could or should be done.

Bluntly, I cannot picture a world where New College shifts to being dominated by conservatives. What I can picture, and what I hope for, is a world where it shifts to being open to conservatives, where young people eager to study the great works of history and to embrace a liberal arts education can do so in an environment that does not demand rigid adherence to progressive tenets. Perhaps that 12 to one ratio among faculty can shrink to, say, four to one. Stranger things have happened.

The answer to bias isn’t only a different kind of bias. But in an ecosystem where virtually every liberal arts college is overwhelmingly biased in much the same way, having a few to sing the counter-melody can help.

Conclusion

I don’t particularly like or trust Ron DeSantis. I feel for the students and faculty at New College, thrust into an experiment they neither expected nor wanted. And I have no idea whether the board members DeSantis appointed can succeed at their stated goal. Shifting an institutional culture, especially one that does not want to be shifted, is difficult, as is finding qualified thinkers capable of both supporting the culture Rufo and DeSantis envision and fostering the atmosphere of truth-seeking and intellectual curiosity necessary to be valuable as a university.

I will be rooting for them, though, and I have already seen a few moments to appreciate, such as when Rufo shut down a heckler’s veto in advance of his remarks to faculty. In the scheme of things, New College is a tiny, struggling university. Seven hundred students, somewhere around 1% of the size of University of Florida. Whatever happens there is unlikely to change much beyond its walls. A world in which conservatives make a serious effort to re-engage with the humanities and seek to cultivate more universities that challenge and test the underlying assumptions in liberal culture, though, is one that would be good for conservatives and liberals alike. This is, perhaps, one step towards that. It might even go well.

I’m here subscribing to you after reading this on BAR. Thank you for this optimistic and hopeful take. I often think Jesse and Katie are too careful in their pushback against woke policies/culture. I personally feel assaulted by the culture in which my kids are coming of age and on certain days I definitely am too angry to be effective. On those days I am thankful for the reasoned approach - BAR lets me laugh and calms me down.

But I’m also tired of being careful - the only way these topics will get into the mainstream conversation , given MSM, is for top-down policies like this. It is not safe for there to be so few people questioning the woke agenda. It is sneaking in and becoming codified because they don’t see through the language: “ obviously we want to be inclusive” and “I want more people to have happier lives so... equity.” The less thoughtful / more reactive parents around me are not thinking things through. The ones who are live in fear of others canceling them or their kids.

We’re need more examples of open pushback. UTAX is a hopeful project but it is too small. I am grateful to see existing universities create new heterodox spaces and programs. Very grateful.

Congrats on the spiffy new job title! I also had some issues with Katie and Jesse's take, which rightfully got a considerable amount of push back in the comments from people like myself, with recent or current experience in public universities in the South.

I agree with a lot of your take here. On the question of a "takeover" of an existing institution like New College, I think it's an approach that I wouldn't want, except I think shaking things up at some places may be what's needed to make substantial change in the trajectory towards doctrinaire thought at so many universities. As you pointed out with the planned University of Austin (best wishes for them, in all sincerity), trying to get a new university off the ground is extremely challenging, especially, I imagine, in the case of a public school. Would take a lot of political will to found a whole new university when UCF can just add a few thousand more to the roster, not to mention competing against institutions with very established reputations.

I also have to appreciate your shout out to GMU economics. I actually spent my first two years in undergrad studying economics and poly sci at Mason. I ended up having to transfer for family reasons, but I believe I learned a ton there and the perspectives I was exposed to have helped me be a more rigorous and balanced thinker to this day, even if, like you, I don't agree with a lot of the positions of, say, Caplan and Hanson. There is so much to be said for productive disagreement, and I think that's one of the values particularly at stake in academia today. I think you make a really good point about having viewpoint diversity *between* institutions, not necessarily expecting full diversity within each particular school.

I'm not a DeSantis fan (although I think attacks on him often go too far) and definitely not Rufo, I still hope that maybe something good will come of this experiment, or something similar at other schools, especially if it could be accomplished with a wee bit less fanfare.