How Wikipedia Whitewashes Mao

The Anatomy of Ideological Capture

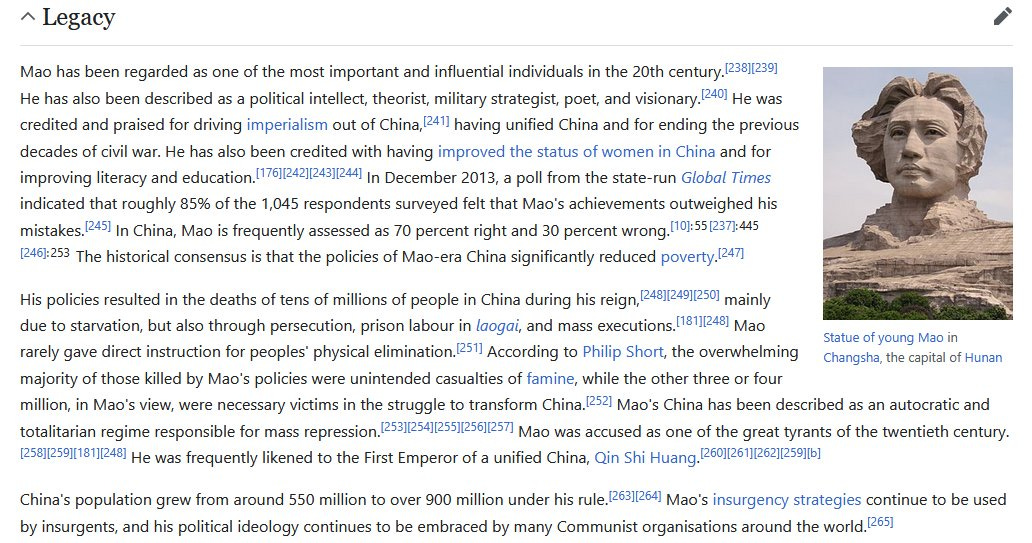

Recently, in a passing aside on Twitter, I tossed out a post making fun of how Wikipedia frames Mao's legacy, assuming that what I saw was self-evident. The current article starts out its legacy section by describing Mao as “one of the most important and influential individuals in the 20th century” who “has also been described as a political intellect, theorist, military strategist, poet, and visionary” and goes through a paragraph of glowing praise before mentioning his mass killings. Once it describes the killings, it couches them in a defensive framing.

Here’s the excerpt:

Mao has been regarded as one of the most important and influential individuals in the 20th century. He has also been described as a political intellect, theorist, military strategist, poet, and visionary. He was credited and praised for driving imperialism out of China, having unified China and for ending the previous decades of civil war. He has also been credited with having improved the status of women in China and for improving literacy and education. In December 2013, a poll from the state-run Global Times indicated that roughly 85% of the 1,045 respondents surveyed felt that Mao's achievements outweighed his mistakes. In China, Mao is frequently assessed as 70 percent right and 30 percent wrong. The historical consensus is that the policies of Mao-era China significantly reduced poverty.

His policies resulted in the deaths of tens of millions of people in China during his reign, mainly due to starvation, but also through persecution, prison labour in laogai, and mass executions. Mao rarely gave direct instruction for peoples' physical elimination. According to Philip Short, the overwhelming majority of those killed by Mao's policies were unintended casualties of famine, while the other three or four million, in Mao's view, were necessary victims in the struggle to transform China. Mao's China has been described as an autocratic and totalitarian regime responsible for mass repression. Mao was accused as one of the great tyrants of the twentieth century. He was frequently likened to the First Emperor of a unified China, Qin Shi Huang.

China's population grew from around 550 million to over 900 million under his rule. Mao's insurgency strategies continue to be used by insurgents, and his political ideology continues to be embraced by many Communist organisations around the world.

I was surprised at the vehemence of the pushback I got. Some of it was inevitable—there are always a few genuine Maoists around—but a lot of generally good-faith left-leaning people in my circles reacted with harsh skepticism. One representative reply from a friend, Elijah, put it like this:

Seeing a holistic picture of a great and terrible figure and responding with rage is what happens when ideological defenses are triggered and feel it necessary to shut down critical thinking. Having this kind of response to this paragraph is a red flag for your reasoning.

Another popular reply came from a self-described “Bernie Sanders–Bill Clinton Democrat”:

I’m genuinely confused by people’s objections to this. Seems like a pretty objective and well balanced account of Mao

And another from a friend, @NaMesoAtta:

this seems pretty balanced to me, especially from a global perspective. It would be one thing if it didn't prominently mention the millions he killed or his abusive totalitarian reign, but it does. It just also mentions other things that undeniably matter historically!

Now, I should be clear that people are absolutely correct to note that I am no fan of Mao. I view him alongside Hitler and Stalin as one of the three most catastrophic leaders of the twentieth century, a murderous tyrant whose greatest contribution to human well-being was his death. But my objection is not that the article doesn’t uncritically represent my own view. I'm not asking Wikipedia to make a prosecutor's case against the man; I can do that myself. I'm upset because the section looks precisely how I would approach a statement were I Mao Zedong's defense attorney.

First: start with glowing praise, every word technically defensible. Lead with all your good facts, looking for every convenient data point or stock line. Phrase them in ways that most everyone reading will instinctively parse as good. He's important, influential. He's a political intellect, a theorist, a military strategist, a poet, a visionary. He drove imperialism out of China, he unified China, he ended civil war (don't press too hard on the details of that war!). Find reforms you can claim for him, find a sympathetic survey or two, note that he reduced poverty. Spend a whole paragraph laying out nothing but praise for him.

But everyone knows he killed people. What do you do with that? Well, any lawyer whose client has some bad facts will tell you precisely what you do with it. You don't hide it—that just lets the other side bring it up. Makes you look dishonest. Be upfront about it, but massage it a bit. Tell the story from your protagonist's view. Make it land smoothly. You start by sandwiching it between good facts, naturally. Everyone's just had a paragraph about how great this guy is. Now you're ready to slide in that tens of millions of people died.

But wait! Mostly, you can add, it was starvation (probably unintentional!), but also, yeah, okay, executions and other mumbling. But he didn't usually give direct orders to kill! And according to one sympathetic writer, most deaths were unintentional, and the rest were "necessary victims in the struggle to transform China." Use his voice! Then, yes, yes, it's been described as autocratic and totalitarian, and people called him a tyrant. Sure, sure, we know this. Anyway, he was compared to the first emperor of a unified China.

Finally, tie it off with a neat bow: Forget about the deaths, the population grew! His strategies continue to be used; his ideology is popular and influential today! It's a picture-perfect defense.

Would it be made stronger by omitting the killings? No! You've given people just enough to say that you're being honest, presenting a nuanced, thorough picture of a complicated man.

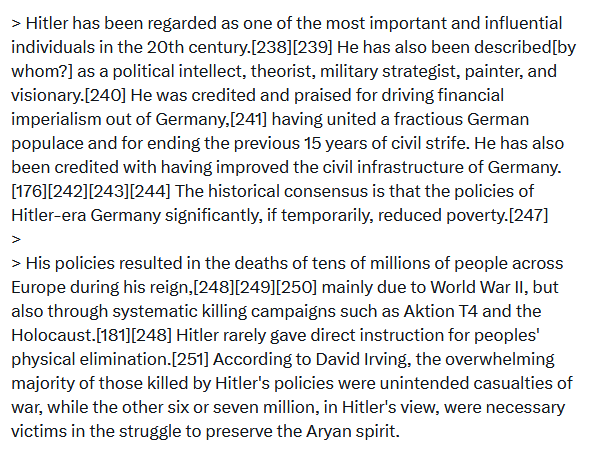

To make the structure more apparent, my friend Tossit provided a parody example using Hitler, describing him as “a political intellect, theorist, military strategist, painter, and visionary […] [whose] policies resulted in the deaths of tens of millions of people across Europe”:

Enough about Mao for now. Some responses objected to the Hitler comparison, asserting that because Mao won and remains popular to many, he should be treated fundamentally differently to Hitler. In some sense, that’s inevitable, bitter as it is to watch people lionize a man who deliberately murdered millions. But the article goes beyond merely treating the successful differently to the unsuccessful. Consider the comparison proposed by some commentators of Spanish dictator Francisco Franco, who ruled Spain from 1939 to 1975.

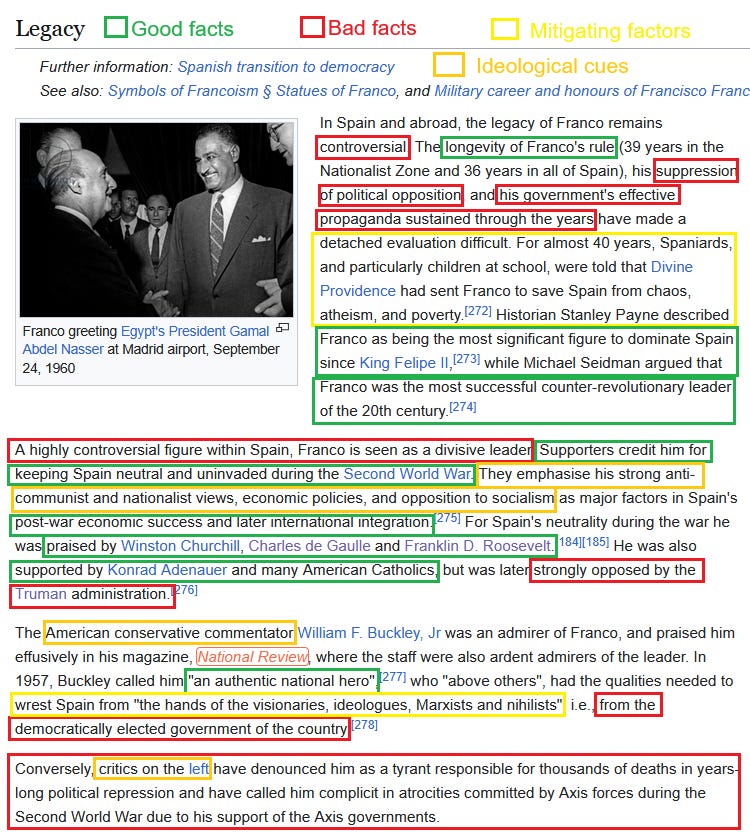

What does it look like when you have a mix of defense and prosecution on a case, with the prosecution winning out? Franco’s legacy demonstrates.

How do things start out this time? He's controversial. He ruled for a long time, he suppressed opposition, he ran propaganda campaigns. Hard to evaluate in a detached way—and look, his citizens were subjected to constant messages that he was good. You can't trust their objectivity! When you praise him, note that he's "significant"—and who can deny that, though it’s not a particularly glowing term—and a successful counter-revolutionary. The last bit carries deliberate ideological loading: good if you hate revolution, bad if you don’t.

None of the glowing praise to start things off. None of the fawning. Mao ran propaganda campaigns as well, Mao suppressed opposition as well—but it only merits mention with Franco.

Moving forward, the article notes again that he's controversial and divisive. It presents the supporter's case, making sure to frame it in ideological terms rather than the absolute-good terms used for Mao's positives. Good if you like anti-communism and nationalism, good if you hate socialism. And supporters credit those ideological stances for Spain's economic success! Add a bit about who praises and supports him and who opposes him.

Next, the article finds someone readers will have particularly divided opinions about, and be sure to contextualize him. While Philip Short is just Philip Short, William F. Buckley, Jr. is an American Conservative Commentator. The section is careful to note that he praised Franco in explicitly divisive ideological terms, and recontextualizes his statement: Franco wrested government "from the democratically elected government of the country."

It then presents the critics' case unsparingly and directly, using examples everyone will agree are bad things: thousands of deaths,political repression, complicity in Axis crimes.

(The legacy section continues for many more paragraphs of minutia, most of it negative.)

Do you see the difference? Do you see the shape of each? Franco is presented unsparingly, his crimes understood, with most praise presented in divisive ideological terms and criticism presented in universal terms. Mao's entry is practically a coronation speech for a paragraph, followed by carefully mitigated bad facts before ending strong.

Is it as simple as going onto Wikipedia to change this? In the wake of my article, one editor tried to make a few tweaks, aiming to add a note (for example) that Deng Xiaoping was the source of the “70% good, 30% bad” claim. Others reverted the change and accused him of beginning “an edit war” within minutes. The article didn’t just happen to land where it did. Any efforts to nudge it elsewhere require someone willing to wrestle for months or years with motivated editors who actively manipulate procedural norms to their advantage and who have both seniority and home-court advantage. Nor do I want to encourage people to edit. Wikipedia editors strongly object to off-site canvassing, and ignoring or trampling their rules only marks someone as an outsider to be dismissed and ignored.

Despite the veneer of editability, these dynamics make the section self-protecting and self-reinforcing. Motivated proceduralists defend it by claiming that it represents the mainstream view, making it good by Wikipedia’s guidelines, then brush over the ways the “mainstream” has entirely reversed itself in fourteen years. Criticizing the page was enough for one proceduralist to take me to task for “try[ing] to destroy one of the only good things remaining on the internet.”

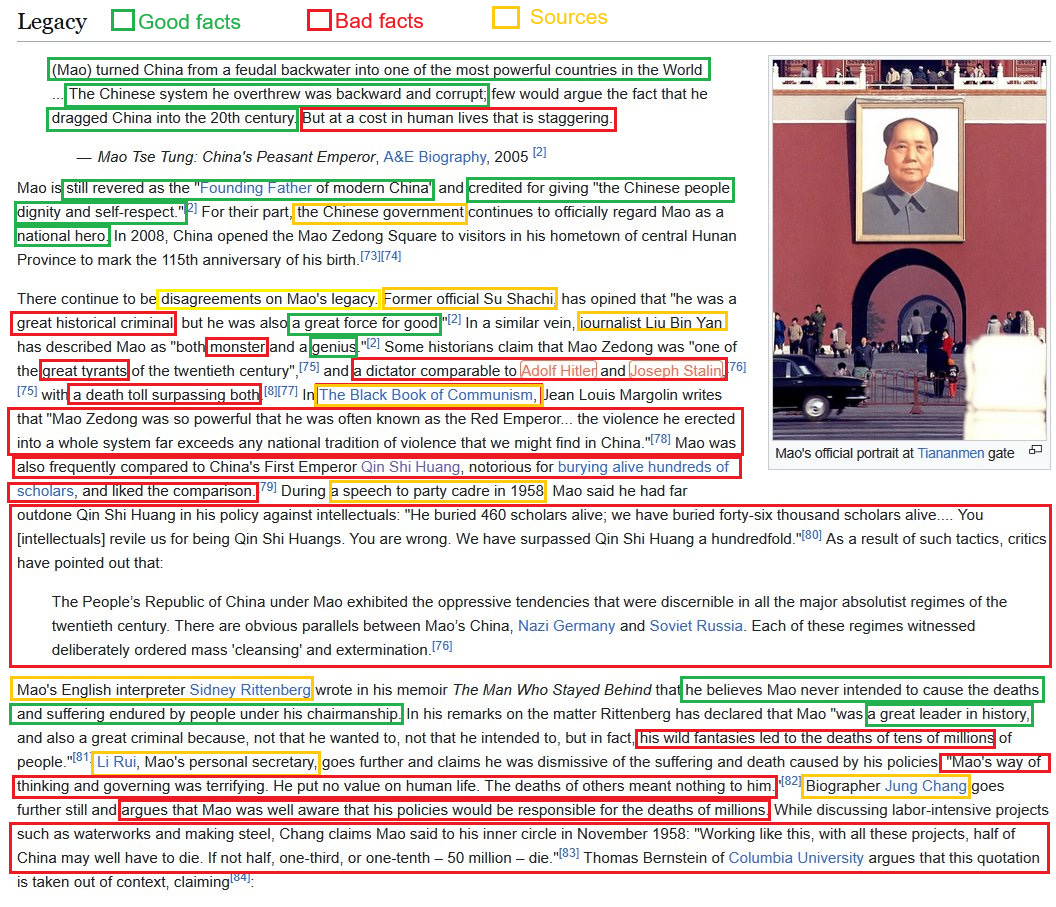

But it was not always like this. Consider the same section of Mao’s page in 2011.

What was Mao’s legacy in 2011? The Founding Father of modern China, yes, credited for giving “the Chinese people dignity and self-respect.” A celebrated national hero according to the Chinese government.

Immediately, it centers his bloodthirstiness and his apathy towards human lives. It quotes Chinese officials and journalists to make the case: a “great historical criminal,” but “a great force for good.” “Both monster and a genius.” “One of the great tyrants of the twentieth century […] comparable to Adolf Hitler and Joseph Stalin, with a death toll surpassing both.” While it shares the reference in the modern page to China’s First Emperor Qin Shi Huang, it draws out the darkness in the comparison: Qin buried hundreds of scholars alive, and Mao bragged that he had “buried forty-six thousand scholars alive […] surpass[ing] Qin Shi Huang a hundredfold.”

The page points to the parallels between Mao’s China, Nazi Germany, and Soviet Russia. It quotes Mao’s English interpreter to note both that he believed Mao did not intend mass death and that he was a great leader, but that he was a great criminal whose “wild fantasies led to the deaths of tens of millions.” It highlights his personal secretary saying that Mao was “terrifying,” that “he put not value on human life,” that “the deaths of others meant nothing to him. And it pulls a quote from a biography of Mao: “Working like this, with all these projects, half of China may well have to die. If not half, one-third, or one-tenth—50 million—die.”

There’s more, but you get the point.

In 2011, the page was a tightly sourced prosecutor’s narrative, one that drew from historians and people in Mao’s inner circle to emphasize the man’s bloodlust and his indifference to human life. By 2025, the same section is a hagiography.

I earnestly and emphatically believe Mao merits mention in the same breath as Stalin and Hitler, but my position is not that Wikipedia ought be controlled only by my understanding of him as a moral monster. If the section had wound up looking like a wrestling match between my own view and the Maoist one, I would have raised an eyebrow a bit and moved on. That’s not what happened, though. Between 2011 and 2025, the legacy section became Maoist propaganda, and when I pointed it out a flood of people—including some I trust to be both earnest and acting in good faith—told me I was being ridiculous and that the page looked reasonable and balanced.

If someone thinks that article is balanced, I hate to imagine what they think praise of Mao would look like.

Wikipedia spent a long while building up a store of goodwill and trust. Now, motivated editors burn that trust by doing things like spending a decade transforming the site’s presentation of Mao’s legacy from condemnation to hagiography. As long as every word remains technically defensible and the mass murders get passing mention, people happy with the way it is will mock anyone who criticizes the page, while well-meaning anti-anti-communists with some left sympathies explain politely and patiently that all of those things happened and that wanting a less glowing portrayal amounts to just wanting a mirror of my own views.

But look: you’re all are reading the same article as I am. You're seeing the same paragraphs I am. You're not reading a thoughtful, nuanced, balanced take on a complex individual, you're reading propaganda for a mass murderer. Propaganda does not stop being propaganda because it acknowledges bad facts, and it is not unreasonable to point it out for what it is. A defense attorney does not stop being a defense attorney when they let some criticism slip in. Glowing praise followed by a concession to reality does not a balanced portrait of a mass murderer make.

In 2025, as far as Wikipedia is concerned, the legacy of one of the worst mass murderers in history is now that of “a political intellect, theorist, military strategist, poet, and visionary.”

Had Wikipedia died in 2011, its achievements would have been immortal. Had it died in 2018, it would still have been a great site but flawed. But here we are in 2025. Alas, what can one say?

EDIT: Remsense, one of the editors who participated in this, stopped by with a thoughtful explanation of his own process. I trust his explanation as accurate to his reasoning and think it indicates genuine good faith on his part, and I encourage interested readers to read his comment in full. Wikipedia editors are not a malicious cabal; they’re a community with a range of interests and biases, even as those who lean into or take advantage of biases that do exist, and those who are most persistent, can assert a lot of control within it.

See also Dan Gardner’s response to my article, with a suggested takeaway: “[T]he only way to improve Wikipedia is for more people, of all stripes, to get involved. […] [T]o condemn and abandon Wikipedia is to give up on something beautiful, and push us further along a path whose destination we will all — right, left, centre, whatever — regret profoundly.” His commentary is worth taking seriously.

These days I assume Wikipedia will be completely useless if the topic has an iota of political salience.

This has happened to a lot of good and/or important institutions since the mid 2010s. People keep blaming the trust crisis on conspiracy theorists and misinformation, but it’s this. I know these institutions are essentially trying to trick me for political purposes, even when I don’t yet know how or even why. And I’m a liberal (or was in 2012), imagine how conservatives and the uncommitted feel.